“그저 그리다”

박경률 개인전: 날마다 기쁘고 좋은 날_신승오(페리지갤러리 디렉터), 2025

"Just Painting"

Park Kyung Ryul’s Solo Exhibition Every Day, A Good Day

Shin Seung Oh (Director, Perigee Gallery), 2025

“그저 그리다”

박경률은 회화의 역사를 통해 구축되어 온 방법론을 되짚어보면서 ‘무엇이 회화가 되는가?’ 라는 화두를 바탕으로 작업을 해왔다. 그것은 정규 미술교육을 받으면서 본인에게 흡수되어 체화된 방식을 하나씩 들추어내어 무의식적으로 대상을 재현하거나 화면을 소위 조화롭게 구성하는 방식, 작가 자신의 경험을 통해 펼쳐지는 서사를 의식적으로 배제하려는 태도이다. 여기에 더해 작가의 붓질, 물감이 가진 물성, 이를 지지하는 천에 이르는 재료를 통해 나타나는 회화에서 하나의 사물과 같은 존재감을 가질 수 있는지에 대한 가능성을 모색하고 있다. 3점의 작품 모두 <생활>이라는 이름으로 구성된 《날마다 기쁘고 좋은 날》은 지금까지 그가 순차적으로 진행해 온 실험을 하나로 모아 ‘그리기’ 그 자체에 집중해 보는 전시로 볼 수 있다.

먼저 가로로 긴 5개의 화면으로 이어진 작품을 살펴보자. 이 대형 작품은 한눈에 모든 장면이 들어오지 않아서 이를 제대로 보기 위해서는 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로, 혹은 반대 방향에서 움직이면서 감상하게 된다. 물론 한자리에 앉아 시선을 옮기는 방법도 있을 것이다. 화면은 왼쪽의 푸른 화면이 오른쪽 사선으로 점점 내려가면서 반대로 점점 하얀 표면이 확장된다. 반대로 운동감을 가진 흐름이 보여주는 방향성은 화면의 오른쪽 하단에서 왼쪽으로 이동하는 형국이다. 그러나 그 안에 보이는 붓질과 어떤 모습을 가진 대상은 이런 흐름과는 상관없이 존재한다. 그리고 화면 전체는 여러 가지 선, 면 그리고 다양한 색으로 가득 채워져 있다. 이들은 처음엔 두드러진 형상과 색으로만 보이다가, 점점 면과 선에 의한 흐름과 질감을 보여준다. 또 한참을 보고 있으면, 그 하나하나의 붓질에 의해 만들어진 정확한 언어로 표현하기 힘든 보이지 않던 형태가 유령처럼 자신의 모습을 드러낸다. 이렇게 그의 화면 안에서는 그 자체로 부드럽게 존재하는 투명함을 볼 수 있는데, 이는 붓질에 의해 덧씌워지더라도 가려지기보다는 서서히 도드라지는 모습이다. 이러한 효과는 당연하게도 그의 붓질이 가진 빠름과 느림의 속도, 강하고 약한 강도, 방향성을 자유자재로 사용하는 것에 기인한다. 그리고 이러한 붓질은 무엇을 덮어 사라지게 하는 것이 아니라 덧붙임과 같은 방식으로 이루어진다. 따라서 그의 작업에 등장하는 모든 것들은 한정된 하나의 차원이 아니라 어디에도 존재할 수 있는 느슨하면서도 긴장감을 가진 존재적 자유로움을 가진다. 그렇다고 해서 이와 같은 복잡한 그림이 무질서함과 근원적인 형태 없음을 의미하는 것은 아니다. 이처럼 우리가 볼 수 있는 화면에서의 흐름은 작가에 의해 ‘없음’에서 시작되어 그 자체로 하나의 질서를 새롭게 생성하고, 하나의 전체를 다시 설정하는 어떤 존재들의 ‘있음’을 만들어 낸다.

다른 <생활>의 화면에도 분명한 지향점이 있어 보이나 그것의 결과물은 불명확한 채로 표현된다. 이는 고정된 완성인 그림이 아니라 ‘그리기’라는 행위를 바탕으로 하는 유동성을 지향하기 때문이다. 작가에 의하면 작품의 제목인 ‘생활(生活)’에서 ‘생’은 그리기를 통해 무엇인가를 생성하게 하고 ‘활’은 그것을 지속적으로 활성화하는 것이라고 이야기한다. 이렇게 본다면 그가 집중하고 있는 그리는 행위는 ‘활’이 가진 끊임없는 유동성에 대한 관심이다. 과연 회화는 작가의 의도대로 완성을 계속 유보하는 유동적 상태로 남겨질 수 있을까? 그리고 이를 통해 무엇을 획득할 수 있을까? 다시 그림을 살펴보자. 그림 안에서 그의 움직임은 확장되다 막히고, 다시 우회로를 찾고, 미궁에 빠지다가 어딘가로 벗어나려는 것처럼 보인다. 여기서 중요한 것은 빈 화면에 개입하여 그리는 동안 모든 것이 이어져 붓끝에 전달되어 생성되는 것을 어떻게 화면에 최대한 남길 수 있는지이다. 그것은 어떤 고정된 의미도 담지 않을 것이고, 우리가 확신할 수 있는 것은 다음 붓질에서 다시 모든 것이 새롭게 시작될 것이라는 점 하나이다. 그리고 그것은 평온한 조화이거나 혼란스러운 부조화로 나타날지 예측하기 힘든 개별적인 존재의 모습만을 남기게 된다. 그렇다면 그가 예민하게 반응하는 회화라는 시간과 공간에서 펼쳐지는 그리는 행위는 어떤 구체적 서사가 아니라 물질과 감각이 하나 된 혼합체가 아닐까? 물론 누군가는 화면에는 작가의 경험을 담은 것처럼 보이는 명확한 형상이 분명 존재한다고 반문할 수 있을 것이다. 그러나 그는 일상적인 지극히 개인적인 이야기, 다시 말해 어떤 삶을 경험한 목격자이자 그것을 기록하여 들려주는 역할을 하려 하지 않는다. 그저 작가는 그리는 행위를 통해 비로소 나타나는 모든 것을 생략하거나 누락시키지 않고 우리에게 시각적으로 고스란히 남기는 행위자가 되고자 한다. 그렇기에 그것이 정확하게 어떤 형태를 가지든 추상적인 움직임으로 남든 혹은 어떤 의미를 담고 있는지는 작가에게 중요하지 않다. 따라서 그에게 그린다는 것의 유동성은 아직 나타나지 않아서 아무것도 구체적으로 형용할 수 없는 무형의 것을 시각적으로 물질화하는 것을 의미한다.

그의 작업에서 살펴봐야 할 또 다른 요소는 시간성이다. 시간은 무엇인가를 존재하게 하는 고정된 지표로 작용한다. 그런데 그의 그림의 표면을 보면 그가 그리는 것들은 단단해지기보다는 부드러워지고 있는 것처럼 보인다. 하지만 그것들이 용해되어 서로 분간할 수 없을 정도로 뒤섞이는 혼돈이 아니라 명확하게 각자가 존재하는 그 잠정적인 순간을 드러낸다. 이는 결국 어떤 형상처럼 온전히 굳어진 것이 아니라 유의미한 것이 무의미한 것으로 무의미한 것이 유의미한 것으로 서로의 몸을 반쯤은 삼켜버린 모호한 상태이며, 이것이야말로 작가가 의도하고 있는 무엇인가 계속해서 존재하도록 하는 활(活)의 모습이 아닐까? 이렇게 시간은 그에게 모든 것이 나타나는 말랑말랑한 형식이 된다. 물론 그에게는 그리는 형식이 중요하지 않지만 사실상 그가 해오고 있는 작업 그 자체가 어떤 형식으로 보이는 것도 사실이다. 그렇지만 그는 그리는 행위를 반복하며, 그 경계에 머물지 않으려 한다. 이는 작가가 작업을 통해 그리기의 흔적이 생성하는 자연스러운 존재의 궤적을 넓히고 축적하기 위해 취하는 태도이다. 그러나 그의 그림에서 나타나는 시간의 물질화는 무엇인가 아름다운 순간이나 나에게 어떤 자극을 유발하여 기억에 남기는 순간 같이 특정하게 남겨지는 시간이라고 볼 수 없다. 오히려 작가는 그 시간 이후에 나에게서 멀어져 온전히 보존되지 않고 수정, 겹침, 삭제, 첨가와 같은 점진적으로 일어나는 변화의 순간을 받아들인다. 이런 상황이 발생하는 순간은 작가를 평소와는 다른 층위의 시간으로 전이하게 만든다. <생활>처럼 그가 선호하지 않는 가로로 긴 화면이라는 프레임도 하나의 예가 될 수 있다. 그에게 익숙하지 않은 거대한 화면을 마주한 순간 자연스럽게 기존의 붓질과는 다른 접근이 필요하고, 이에 따라 기존에 축적된 인식의 체계를 벗어나 이질적인 것들로 채워져 활기가 넘치는 새로운 시간성을 획득하게 된다.

그렇다면 우리는 그의 작업을 어떻게 보아야 할까? 물론 우리는 결과론적으로 그의 그림을 보면서 연상할 수 있는 것을 도구로 사용해 관습적으로 그것을 읽어내려 할 것이다. 그리고 작가가 마주치는 여러 요소에 직접적으로 접촉하거나, 눈으로 보거나 냄새만 맡거나, 스쳐 지나가거나 어떤 지표가 되는 것에서 기인한 무엇인가가 드러나는 것으로 상상해 보게 된다. 그러나 그가 그리는 행위로 나타나는 점, 선, 면 그리고 색은 무의미한 것으로 아무것도 되려 하지 않는다. 그렇기에 그의 작업은 어디론가 이어져 무엇인가를 전달하는 매개체도 아니고, 우리가 분명 도달해야 할 목적지도 아니다. 그에게 한 개인으로서 경험하는 선형적인 시간의 흐름은 무의미하다. 작가는 계속되는 변화의 시간을 마주하여 그것을 자신의 회화에 붙잡아 다시 새롭게 복원해 내는 활동만 남기려 한다. 왜 그는 그것을 그토록 붙잡아 놓으려 하는가? 우리에겐 지나간 것과 다가오는 것이 만날 수 있는 토대가 필요하며, 그 위에 자신의 개별적 삶에 기인하지만, 그것에서 한참 벗어난 별개의 세상을 세울 수 있기 때문이다. 그것들은 그의 작업과 같이 무작위적인 것 같지만, 차곡차곡 쌓여 나가고 있으며, 이는 그림을 그리는 작가의 시간도 다르지 않다. 따라서 우리는 그의 그림을 보면서 있는 그대로의 것을 억지로 조화롭게 하거나 부자연스러운 것을 외면하지 않고, 흐름을 따라 고스란히 그 안에 스며들 시간이 필요하다. 하지만 작가가 사실상 영원히 도달하지 않으려는 이러한 회화를 온전히 따라가는 것은 모호함이 가득 찬 시공간을 마주하는 혼란스러운 일이 될지도 모른다. 그런데도 우리가 보는 것은 그것의 물성, 색, 질감, 움직임, 형태, 맥락, 구성과 같은 나열된 형상의 밖을 둘러싸고 있는 표면일 뿐이다. 그래서 우리는 다양한 요소들이 연결된 하나의 통합적 대상과 이들과 분리되어 스스로 존재하는 개별적 대상을 동시에 인식하려는 태도가 필요하다. 우리가 박경률의 화면과 관계를 맺는다는 것은 그의 그림을 이루고 있는 모든 것이 한자리에 옮겨지면서 일어나는 접촉과 마찰의 결과가 불러일으키는 느낌일 수도 있겠다. 그리고 거대한 것에서부터 작은 것, 가느다랗고 얇은 것에서 두꺼운 것, 직선적인 것에서부터 곡선적인 것까지 하나도 지루할 틈 없는 붓질의 시간은 그저 존재의 한 조각으로 남는다. 그렇기에 우리가 작가의 의도를 가진 본능적 붓질로 남겨진 존재 하나를 인식하게 되면, 갑자기 선명하게 눈 앞에 펼쳐지게 된다.

이제 전시 제목인 《날마다 기쁘고 좋은 날》로 돌아와 보자.우리 모두 알다시피 우리가 존재하는 세계는 여러 사물의 총화로 이루어진다.그가 무엇인가를 그리는 과정에 따라 나타나는 모든 것을 그저 담고 있을 뿐인 그림도 이와 다르지 않다.이렇게 그는 그리기의 결과 보다는 그 행위 자체에 온전히 자신이 빠져들어 그 어떤 것도 의식하지 않는 순수한 붓질을 하나라도 더 만들어 내길 바란다.따라서 그가 말하는‘날마다 기쁘고 좋은 날’은 그가 삶의 순간으로 그리면서 살아가는 그 순수한 몰입의 시간을 의미하는 것으로 보인다.그렇지만 그에게 그리는 것은 어떤 특별한 행위가 아니다.그것은 현실이라는 실재와 유리된 것이 아니라 한 번의 붓질이 하나의 현존재로 나타나게 하는 일이다.이는 지루하고 평범한 시간의 흐름에서 벗어나 반짝이는 한 조각의 물질들로 이루어진 회화로 펼쳐진다.이와 같은 그리는 행위는 그에게 우리의 삶에 자유로운 공기를 주입하는 것,그래서 말로 설명하기 힘든 희열을 맛보게 하며,그가 유한한 삶을 통과하며 시공간과 교감하는 방식이다.이처럼 그의 작업이 지속될 수 있는 것은 내일은 오늘과 다른 새로운 시간이 열리고 그릴 때마다 존재들은 계속해서 드러나기 때문일 것이다.결국 이번 전시에서 그는 모든 것을 떨쳐낸 복잡하고 무겁지 않은 가벼운 그리기의 방식에 집중하고 있다.이를 바탕으로 박경률의 회화는 온전히 붓끝의 움직임으로 비로소 생성되는 물질 그 자체로 남으려 하는 본인의 의도에 한 발 더 다가서려 한다.이제 다시 그의 그림으로 돌아와‘나’에게 아직 익숙하지 않은 시선으로 그의 그림을 충분히 눈에 담길 바란다.그런 후에 서서히 익숙해지며 드러나는 그 존재들을 하나씩 채집하여 이리저리 보며 즐길 수 있다면,이전과는 달라진 눈을 통해‘그저 그리기’의 본질을 마주할 수 있을 것이다.

"Just Painting"

Park Kyung Ryul has been working with the fundamental question "What constitutes painting?" while reexamining the methodologies established throughout the history of painting. Her approach involves consciously excluding the unconscious representation of subjects or the so-called harmonious composition of the canvas that has been absorbed and embodied through formal art education. Additionally, she explores the possibility of achieving an object-like presence in painting through the painter's brushwork, the materiality of paint, and the supporting canvas material. The exhibition "Every Day, A Good Day," consisting of three works all titled “생활” (Saeng-Hwal) can be viewed as a show that focuses on the act of painting itself by bringing together the experiments she has been conducting sequentially until now.

Let's first examine the work that consists of five horizontally connected canvases. This large-scale work cannot be taken in at a single glance; to properly view it, one must move from left to right, or in the opposite direction. One could also remain in one spot and simply shift their gaze. The blue surface on the left gradually descends diagonally toward the right as the white surface expands in the opposite direction. Conversely, the directionality shown by the flow with kinetic energy takes the form of movement from the lower right of the canvas toward the left. However, the brushstrokes visible within and any subjects with particular forms exist independently of this flow. The entire canvas is filled with various lines, planes, and diverse colors. These initially appear as merely prominent figures and colors, but gradually reveal flows and textures created by planes and lines. After prolonged viewing, forms that were previously invisible and difficult to describe in precise language emerge like ghosts through individual brushstrokes. In this way, one can observe a transparency that exists softly in her canvas, which, rather than being concealed when overlaid with brushstrokes, gradually becomes more pronounced. This effect is naturally attributed to her masterful use of brushwork's speed (fast and slow), intensity (strong and weak), and directionality. Furthermore, these brushstrokes don't cover and erase but rather add in layers. Consequently, everything that appears in her work possesses an existential freedom that can exist anywhere, maintaining both looseness and tension, rather than being confined to a single limited dimension. However, this complexity doesn't imply disorder or a fundamental formlessness. The flow we can observe on the canvas creates an existence of beings that starts from nothingness by Park, generates its own new order, and reestablishes a whole.

The other canvases of “생활” (Saeng-Hwal) appear to have clear directions, yet their results remain ambiguous. This ambiguity stems from their aim for fluidity based on the act of painting rather than being fixed, completed paintings. According to Park, in the title “생활”, 생 (生, creation) refers to generating something through painting, while 활 (活, activation) means continuously activating it. From this perspective, the act of painting she focuses on reflects her interest in the constant fluidity of 활 (activation). Can painting truly remain in a fluid state that continually postpones completion as the painter’s intends? And what can be gained through this process? Let's look at the painting again. Her movements within the painting appear to expand then become blocked, find detours, get lost in a maze, and then try to break free somewhere. What's crucial here is how to maximize the preservation on canvas of everything that is generated and transmitted to the brush tip while intervening on the empty canvas during the painting process. It will not contain any fixed meaning, and the only certainty is that everything will start anew with the next brushstroke. This leaves only the appearance of individual existence, which is difficult to predict whether it will manifest as peaceful harmony or chaotic disharmony. Could her sensitive response to the act of painting unfolding in time and space be a hybrid of material and sensation rather than any specific narrative? Someone might counter that there are clearly visible forms on the canvas that seem to contain the painter's experiences. However, she does not attempt to be a witness who has experienced some everyday, deeply personal story, nor to play the role of recording and telling it. Park simply aims to become an agent who visually preserves everything that appears through the act of painting, without omission or abbreviation. Therefore, whether it takes a precise form, remains as abstract movement, or carries any meaning is not important to her. For Park, the fluidity of painting means visually materializing the intangible that has not yet appeared and cannot be specifically described.

Another essential element to examine in her work is temporality. Time acts as a fixed indicator that brings things into existence. However, looking at the surface of her paintings, the things she paints appear to be becoming softer rather than hardening into permanent forms. Yet they reveal that tentative moment where each element clearly exists distinctly, rather than dissolving into chaos where everything becomes indistinguishably mixed. This ultimately represents an ambiguous state where the meaningful and meaningless partially consume each other's bodies - where the meaningful becomes meaningless and the meaningless becomes meaningful - rather than solidifying completely into some form. Isn't this precisely the appearance of 활 (activation) that the artist intends, where something continues to exist? In this way, time becomes a malleable form through which everything appears. While form is not important to her, it's true that her work itself appears to take on a certain form. However, she repeats the act of painting, trying not to remain within those boundaries. This is the attitude she takes to expand and accumulate the natural trajectories of existence generated by traces of painting through her work. The materialization of time that appears in her paintings cannot be seen as specific moments that remain as beautiful instances or moments that stimulate and stay in memory. Rather, Park accepts the moments of gradual change that occur through modification, overlapping, deletion, and addition—moments that aren't fully preserved and become distant from us after that time. When these situations occur, they transport her to a different level of time than usual. The horizontally long frame of “생활” (Saeng-Hwal) which she doesn't prefer, serves as an example. When faced with an unfamiliar enormous canvas, a different approach from her usual brushwork naturally becomes necessary, and consequently, she acquires a new temporality full of vitality, filled with heterogeneous elements that deviate from the previously accumulated system of recognition.

So how should we view her work? Naturally, we will try to read it conventionally, using as tools whatever we can associate with her paintings from a consequential perspective. We begin to imagine something emerging that originates from various elements she encounters—whether through direct contact, visual observation, merely smelling, passing by, or serving as some kind of index. However, the points, lines, planes, and colors that appear through her act of painting remain meaningless, trying to become nothing. Therefore, her work is neither a medium that connects somewhere to convey something, nor a destination we must clearly reach. As an individual, the linear flow of time she experiences is meaningless. Park only tries to leave behind the activity of recapturing and newly restoring the continuous changing time that she faces in her paintings. Why does she try so hard to hold onto it? We need a foundation where the past and the future can meet, and upon that foundation, we can build a separate world that, while originating from one's individual life, has strayed far from it. Like her work, these may seem random, but they are steadily accumulating, and the artist's time spent painting is no different. Therefore, when looking at her paintings, we need time to naturally seep into them, following their flow without forcibly trying to harmonize things as they are or ignoring what feels unnatural. Following such painting that the artist essentially never intends to complete might be a confusing experience of facing a space-time filled with ambiguity. Nevertheless, what we see is merely the surface surrounding the enumerated forms—their materiality, color, texture, movement, form, context, and composition. Therefore, we need an attitude that simultaneously tries to recognize both an integrated object where various elements are connected and individual objects that exist independently, separated from these elements. Our relationship with Park Kyung Ryul's canvas might be the feeling evoked by the result of contact and friction that occurs when everything constituting her painting is transferred to one place. And the time of brushstrokes—from the enormous to the tiny, from the thin and slender to the thick, from the linear to the curved—leaves no room for boredom and remains as just a fragment of existence. Therefore, when we recognize one existence left by the painter's instinctive brushstrokes carrying her intention, it suddenly unfolds clearly before our eyes.

Now, let's return to the exhibition title "Every Day, A Good Day." As we all know, the world we exist in is made up of the sum of various objects. Her paintings, which simply contain everything that appears according to her painting process, are no different. In this way, she desires to create even one more pure brushstroke where she becomes completely immersed in the act itself rather than the result of painting, unconscious of anything else. Therefore, her "Every Day, A Good Day" seems to signify that pure time of immersion as she lives through painting moments of life. However, painting for her is not some special act. It is not something detached from the reality of the real world, but rather an act that makes each brushstroke manifest as a present existence. This unfolds as painting composed of shimmering fragments of matter, breaking away from the flow of boring, ordinary time. Such an act of painting is, for her, a way of injecting free air into our lives, causing indescribable euphoria, and her method of communing with space-time as she passes through finite life. Her work can continue because tomorrow opens up new time different from today, and beings continue to reveal themselves with each painting. In this exhibition, ultimately, she concentrates on an unburdened approach to painting that has shed all excess, embracing simplicity rather than complexity. Based on this, Park Kyung Ryul's paintings attempt to move one step closer to her intention of remaining purely as the material itself that is finally generated by the movement of the brush tip. Now, I hope you will take in her paintings sufficiently with eyes that are still unfamiliar to you. If you can then collect and enjoy examining each being that gradually reveals itself as it becomes familiar, you will be able to face the essence of just painting through eyes that have changed from before.

네시

박경률 개인전: 네시_권태현 (큐레이터), 2024

Four O’Clock, or Nessie

Park Kyung Ryul’s Solo Exhibition Nessie

Kwon Taehyun, Curator, 2024

4시

4:35, 14:10, 16:05… 박경률이 최근에 그린 그림들에는 시간이 제목으로 붙어있다. 짧은 타임코드들은 그가 붓질은 멈춘 시간을 기록한것이다. 그런 제목들은 얼핏 그림은 언제 완성되는가 하는 선문답 같은 질문을 던지는 것처럼 보이지만, 그 방법론은 그림에 도가 튼 화백이 이정도면 되었다 하면서 붓을 내려놓는 형상과는 전혀 다른 곳을 향한다.

박경률의 작업을 만난 경험이 있는 사람이라면 회화와 함께 공간에 펼쳐놓는 사물들을 기억할 것이다. 회화의 조각적 확장 같은 식으로받아들여지기 쉬운 그 특유의 방법론은, 사실 그림 속 형상들을 화면 바깥으로 꺼내는 것이라기보단 오히려 캔버스와 안료의 결합을 조각적인배치로 이해하는 관점에 가깝다. 그는 회화를 구성하는 모든 요소들을 존재론적 차원에서 평등하게 받아들이려고 노력한다. 그리기라는관습에서 벗어나 붓질을 특정한 시간과 공간 속에 물질을 배치하는 움직임으로 이해하는 것이다. 이런 방법론을 통해 박경률에게 그리기란애초에 물질을 어딘가에 두는 행위가 되고, 그렇기에 화면 바깥에 꺼내 놓는 사물들 역시 붓질과 같은 위상에 놓인다. 이렇게 확장된 회화라는매체 탐구의 차원이 아니라, 물질적 평등함이라는 문제에서 박경률의 작업을 보았을 때, 기존의 관점과 다르게 작동하는 지점들을 발견할 수있다. 거기에서 펼쳐지는 감각적 장에는 관객의 움직임, 빛, 중력, 그리고 이번 전시의 맥락에서는 무엇보다 시간이 캔버스나 안료와 같이회화적인 요소로 균질하게 수용된다.

특히 여기서 선보이는 작업들 중 일부는 미국 서부의 한 레지던시에 입주했던 기간에 그린 것들인데, 박경률은 천장이 유리로 되어 있는 그곳스튜디오의 건축적 특성과 캘리포니아의 바삭바삭한 햇볕이 물질을 감각하는 방식에 미친 영향을 중요하게 회고한다. 시간에 따라 변화하는자연광이 자신의 회화적 선택에도 끊임없이 영향을 준다는 사실의 자각은, 우선 그리기라는 행위가 기후나 천체의 운행과 같은 거시적인사물들의 네트워크와도 연결되어 있다는 인식과 연결된다. 미시적으로는 그리기라는 행위를 환경과 운동과 시간의 연쇄, 다시 말해 사건이라고할 수 있는 위상에 가져다 놓을 수 있는 틈이 그곳에서 벌어진다.

사건으로서의 회화. 문제는 이러한 물질적 연쇄로서의 사건이 예술가가 그림을 완성한 이후에도 계속된다는 점에 있다. 그렇기에 멈춰 있던타임 코드는 전시라는 다른 맥락의 시간과 공간에서 다시 움직이기 시작한다. 무엇보다도 각기 다른 관객들의 시간을 만나면서. 그렇게 전시는여러 사건들이 서로 맞물려 작동하는 또 하나의 사건이 된다.

Nessie

괴물이 있다고 믿는 사람은 (혹은 진심으로 믿지 않는다고 해도 어떤 전설을 알고 있다는 사실만으로도)

아무것도 없는 호수의 찰랑거리는 표면에서 계속 괴물을 발견한다. 호수뿐만이 아니다. 우리는 언제나 있는 그대로를 보지 못한다. 애초에무언가를 있는 그대로를 볼 수 있는 사람은 없다. 우리는 항상 구조를 통해서 본다. 눈이라는 기관은 광학적으로 물질적 대상의 형체를받아들일지 몰라도 그것을 최종적으로 처리하는 뇌는 그것이 이미 알고 있는 체계로 대상을 번역한다. 우리가 눈으로 보고 머리 속에 떠올리게되는 이미지는 말 그대로 우리 상상(imagine)의 산물이란 말이다.

박경률은 자신의 화면에 구체적인 형상을 드러내려고 하지 않지만, 우리는 계속해서 어떤 형상들을 발견한다. 그가 아무리 물질과 붓질만을이야기해도 우리는 그것을 기존의 회화를 보는 관습적 태도로 감각하는 것이다. 진정 어떤 의도도 없이 우연적으로 발생한 추상적인 물질적배치라고 해도 우리는 그것을 언어적으로 읽어낼 수 있는 어떤 형상으로 수렴시키거나, 이해할 수 있는 형상으로 번역하곤 한다. 박경률이아무리 자율적으로 손을 움직이며 구조에서 벗어나려고 해도 관객들은 화면에서 어떤 표정을, 유령을, 무지개를, 레몬을, 군상이나 흉상을, 체스말을, 또 괴물을 발견하게 된다. 때로는 같은 형상을 보고도 각기 다른 낱말을 떠올리기도 한다. 심지어 사람들은 그 형상들을 연결하며어떤 이야기를 만들어낸다. 박경률이 작가 노트에서 홀리스 프램튼을 인용하며 말하듯 서사는 구체적으로 있는 것이 아니라, 유령처럼존재한다. 여기에서는 그림과 물질에 대해 이야기하고 있으니 조금 더 만질 수 있는 형태로 존재하는 괴물이라고 해보자.

또 하나의 문제는 회화가 단순히 캔버스에 안료를 올려 만든 물건에 머물지 않는다는 점이다. 그것은 물질적 형식이면서 동시에 지적이고담론적인 형식이며 역사와 전통의 산물이기 때문이다. 이러한 점은 회화가 인식되는 차원에 얽혀 있는 다양한 층위의 구조가 함께 작동한다. 갤러리에 걸린 회화를 볼 때, 관객들은 화면의 형상을 읽어내려고 애쓰면서 동시에 추상이니 구상이니, 모더니즘이니 지지체니 하는 온갖기존의 구조적 연결 속에서 그 대상을 인식하게 된다. 유령처럼, 또 괴물처럼 자꾸만 출몰하는 것은 서사나 형상뿐만이 아니다.

회화라는 사건 안에서 반복적으로 드러나는 형상들, 유령들, 혹은 괴물들. 전시 곳곳에 흩어져 있는 붓질들에서 비슷한 형상이 튀어나올 때마다하나의 완성된 회화의 모습을 온전히 기억하고 상상해 내기가 어려워진다. 이곳 전시장에 늘어놓은 회화들의 면면에서 중세 수도사들이 달달외우던 성경 필사본의 귀퉁이에 모습을 드러내는 괴물들이 떠오른다. 기억술을 위한 이미지들. 그러나 박경률의 형상들은 하나의 회화를명료하게 하나의 기억으로 수렴시키는 기억술이 아니라, 오히려 기억을 복수의 것으로 산란시킨다. 이 그림에서 봤던 것이 저 그림에서 다시등장하고, 어떤 형상은 화면 바깥으로 튀어나와 아까 전에 봤던 그림을 다시 돌아보게 만든다. 기억과 상상 속에서 이미지들은 서로 뒤섞여 전시공간에 놓여 있는 회화들은 자율성의 영역을 넘어 서로를 침범하고 있다.

그리고 거울에 비치는 형상들, 그리고 얼굴들. 그러니까 전시를 관람하고 있는 당신의 얼굴은 괴물, 유령, 혹은 사물의 면면들과 함께 거울 속에모습을 드러냈다가 또 이내 사라진다. 사건으로서의 회화는 박경률이 그림을 그리는 상황에 귀속되어 있지 않다. 회화를 사건으로 만드는역량은 작품에 내재되어 있는 것이 아니라, 그 물질을 마주하는 모든 존재들에게 있다. 화가와 관객, 후에 그림을 소유할 사람뿐 아니라 말그대로 모든 존재들. 회화와 그것을 인식하는 존재, 나아가 그 모두가 놓인 상황을 구성하고 있는 물질들까지. 회화는 그렇게 다른 물질들과의동맹 속에서만 사건이 될 수 있다. 붓질과 물질, 형상과 상상, 기억과 서사, 유령과 괴물, 그리고 보는 이와 보여지는 이의 자리를 끊임없이바꾸어가면서 발생할 수많은 사건들을 기대한다.

Four O’Clock

4:35, 14:10, 16:05... Park Kyung Ryul’s recent paintings have time as their titles. These timecodes refer to the moment she declared each painting to be complete. Titling works this way could remind one of Zen koans — “When is a painting truly complete?” — but Park’s methodology is nothing close to such scenes in which the old and wise painter sets down his brush with satisfaction on his face.

People familiar with Park’s art will know how she lays out numerous objects in her exhibition spaces along with her paintings. This methodology could easily be misunderstood as a means of painting’s sculptural expansion, but in truth, her installations are not about bringing the forms inside the paintings outside. They are more about better understanding the composite of canvas and pigments through sculptural arrangement. Park endeavors to treat every element of painting equally from an ontological dimension. For instance, instead of seeing the brushstroke from the framework of painting traditions, she considers the brushstroke as a movement that places matter onto a particular coordinate of time and space. This methodology allows Park to view the act of painting as the action of placing matter onto specific places, and therefore, the objects she places outside of her canvases gain the same status as her brushstrokes. The idea of painting’s expansion implies an investigation of the medium itself, but observing Park’s art from the issue of material equality, one discovers aspects that function differently from preexisting viewpoints. Inside the sensual field unfolding from here, the visitor’s movements, light, gravity, and, most importantly, in the context of this exhibition, time, are received uniformly, just like any other painterly element such as canvas or pigment.

Specifically, some of the works presented here were created during Park’s residency in Southern US, and she reflects upon the influences the studio’s architectural features (it has a ceiling made of glass) and the crisp Californian sunlight had on her ways of recognizing matter with a sense of profound urgency. Park’s realization that daylight — something that changes hour by hour — could influence her painterly choices must have linked with the recognition that one’s act of painting is, in fact, connected to macroscopic networks such as climate and planetary motions. Microscopically, this is where the gap that allows one to place the act of painting onto the status of an event — the chain of environment, motion, and time — opens up.

Viewing painting as event: however, the problem here is that this event as the chain of materials continues even when the artist has finished the painting. Thus, the paused timecodes start ticking again in the exhibition due to its new context of time and space, and more than anything else, by meeting the visitors who each carry unique timescales. The exhibition becomes another event in which numerous events click together like gears.

Nessie

A person who believes in monsters continues discovering creatures from the serene surface of an apparently empty lake, and even for those who do not believe in such, the mere fact of knowing some myths creates the same effect. And it’s not just lakes. We can never see things as they are. This is because humans always see things through a structure. The eye, as the organ, may optically receive the shape of physical objects, but the brain, the final processor, always translates the objects through systems already known to it. In other words, the images we see through our eyes and conceive in our heads are literally the products of our imaginations.

Park strives not to leave any representational form on her canvases, but we continue to see figures from them. No matter how hard she tries to speak exclusively through matter and brushstrokes, we see her works through conventional painting-viewing attitudes. In fact, even if an abstract arrangement of matter were generated arbitrarily and without involving any intention whatsoever, we would still read it as some linguistically interpretable form or otherwise comprehendible shapes. No matter how much autonomy Park allows her hands in the attempt to escape structure, viewers find facial expressions, ghosts, rainbows, lemons, groups, torsos, chess pieces, or monsters on her canvases. Moreover, different people imagine different words even when they see the same form. In some cases, people go as far as to create narratives by linking the forms they discovered. Just as in her artist statement referring to Hollis Frampton, the narrative is not specific and instead exists like a ghost. However, as we discuss painting and physical matter, we may use something more tangible, such as a monster.

Another problem: a painting is always more than a mere object made by coating the canvas with pigment. Painting is not just a format of materials but also an intellectual and discoursive format and a product of history and tradition. Due to this aspect, recognizing a painting involves numerous dimensions and the various levels of structure entangled with them. When confronted with painting in a gallery, the visitor tries one’s utmost to comprehend the forms on the canvas and, in turn, recognizes the work through all kinds of preexisting structural networks such as abstractionism, figurativism, modernism, and Supports; in short, the ghosts and monsters that continually haunt paintings are not limited to narrative and form.

Forms, ghosts, or monsters repeatedly appear in the events of paintings; as similar forms emerge from the brushstrokes scattered across the exhibition, it becomes gradually more difficult to recall and picture one complete painting of hers in the mind. Some parts of the paintings in this exhibition remind one of the monsters Medieval monks drew onto the margins of their bibles that they so devotedly learned by heart. These images were the means of a mnemonics. In contrast, Park’s forms are not the parts of such a strategy that commit one painting into one vivid memory; instead, they scatter memory into multiple instances. For instance, what appeared in one painting would reappear in the next painting, or a form would jump out of one canvas to make the viewer look back at a previous painting. Images mix into each other through memory and imagination, and the paintings on display step over the allowance of autonomy and intrude on each other.

And, regarding the mirrors and the forms and faces reflected in them: as you move through the exhibition, your face appear and disappear in the mirrors along with monsters, ghosts, or parts of objects. Painting as event does not appertain to the situations Park is working on the painting. The capacity that turns a painting into an event is not ingrained in the work itself. It is omnipresent in every being standing before the material artwork. Not just the painter, viewers, and the potential collector, but literally every being: the painting itself, the being that recognizes it, and the various materials composing the situation in which they exist together. Painting can become an event only within the alliance of other physical matter. Brushstroke and matter, figure and imagination, memory and narrative, ghost and monster, and the perceiver and the perceived constantly switch places and generate countless events. A fascinating future awaits.

조각적 회화의 조건: 손으로 머리를 지탱하여, 시선에서 환상으로

박경률 개인전: 환상 한 조각 _ 안소연 (미술비평가), 2021

The Conditions of Sculptural Painting : Supporting the Head with the Hands, from Looking to Illusion

Park Kyung Ryul’s Solo Exhibition Fantavision

Soyeon Ahn(Art Critic), 2021

1.

회화는 “환상”이라고 말하는 그는 지금 파란색 물감을 반복해서 사용하여 어떤 몰입의 강도를 높이고 있다. 세룰리안 블루(Cerulean Blue),망가니즈 블루(Manganese Blue), 프러시안 블루(Prussian Blue) 물감을 조색 없이 캔버스에 올리면서, 그는 회화의 그리드 안에 가둔-나는 “억압”이라는 단어를 쓰고 싶었지만 혹시 모를 오해를 피하기 위해 “가두었다”는 표현을 선택했다- 물감의 자기 본성에 다시 권한을 부여해 보려는 것 같다. 말하자면, 물감의 물질성(materiality)에 주목하는 것으로 이때의 물질성이란 모더니즘 아방가르드 회화에 기원을 둔 레디메이드 재료라는 사물(object)로서의 특성과 철저히 화학적인 물질이면서 고유한 질료(matter)로서의 특성을 아우른다. 게다가 그는 캔버스 또한 하나의 삼차원적 질료나 사물로 인식하는 회화사의 또 다른 바탕에 뿌리를 두고 자신의 회화가 어떻게 하나의 물질로서 현존할 수 있는가를 탐색한다.

⟪환상 한 조각⟫에서는 박경률의 청색 회화가 색채에 대한 강렬한 지각을 유도하고 있으며 150호 동일한 캔버스의 무심한 배열은 구성적인 서사의 순간을 배제하려는 것처럼 느껴진다. 그럼에도 불구하고 붓질로 매개된 임의의 형상들이 곳곳에서 목격되는데, 어떤 것은 매우 익숙한 형태처럼 보이기도 하고 또 어떤 것은 추상적이며 모호한 붓질의 행위로 경험된다. 이로써 특별한 정황이 만들어진다고 볼 수 있는데, 이와 같은 회화 전시의 구체적인 상황에서 질료와 사물, 형태와 행위가 미세하게 동요하며 잠재적인 변환의 가능성을 암시하고 있다는 것이다. 박경률은 “환상”이라는 단어를 써서 자신의 회화가 일련의 요소들을 다루며 차원의 전환을 시도하여 이를 실체화 한다는 (확신에 찬) 가설을 붙들고 있다.

회화가 매체의 순수성에 따라 자율성을 획득한 모더니즘 형식주의의 논의와 매체의 일상적 참조를 통해 회화의 사물성을 획득한 모더니즘 아방가르드의 논의를 임의적 선택과 판단으로 재맥락화 하려는 박경률의 회화에 대한 입장은 다소 선언적이기까지 하다. 그는 “회화는 환상이다”라고 말한다. 이 의미심장한 선언은 “이미지 중심적인 동시대 시각 지형에서 고유 장르로서 회화가 여전히 유효할 수 있는가”라는 작가적 질문에서 모색된 것이며, “오브제로서의 붓질(piece of brushstroke)”을 스스로 인식한 것에서 출발한다.[*⟪환상 한 조각⟫(2021)에 대한 작가 노트 참고] 미리 짐작해 보건대, 애초에 그가 주목하고 있는 것은 “붓질”이며 그것은 오브제이자 행위이고 다수의 차원을 매개하는 “사유체(corps-pensée)”라 할 수 있다.

한편 박경률이 “조각적 회화”라 부르는 것은 회화에 대한 그의 변함없는 신뢰를 드러내는 것으로, 역설적이게도 그것은 조각적 인식을 통한 회화의 성립 조건을 갱신하는데 있다. 지난 세기 회화와 조각 사이에 놓아진 다리를 왕복하면서, 그는 (사물로의) 매체 확장을 조건화 하지 않으며 삼차원의 특수한 사물(specific object)로 규명되는 회화에 집중하기 보다는 매체에 대한 재인식을 통하여 조각적 사유로부터 회화에 대한 변별성을 살피는 듯하다. 말하자면, 그는 작업 과정에서 그가 늘 강조해온 조각적 사물을 비롯해 그것에 대한 삼차원적인 인식이 마침내는 회화적 상태로 귀결되는 흐름과 마주하고 있는 셈이다.

2.

박경률에게 조각적 회화란 무엇일까? 그는 “조각적 회화의 본질은 ‘그리기라는 행위’에 주목한다는데 있다”고 말했다.[*⟪왼쪽회화전⟫(2020)에 대한 작가 노트 참고] 이때의 그리기 행위에서 이루어지는 조각적 인식은, 마치 미니멀리즘 이후 조각적 시도들이 삼차원적 연극성에 몰두했던 것을 떠올리게 하는데, 특수한 사물을 실제 공간에 배열하는 신체의 행위로 유추해 볼 수 있다. 오래된 조각적 환영에서 벗어나 “모서리와 면들을 결합하여 하나의 오브제를 형성함으로써” 실제 공간에서의 실제 재료를 통해 형태의 “사실”을 경험하려 했던 미니멀리즘의 맥락과 비교해 볼 때, 박경률은 물감과 캔버스를 하나의 “물질”이자 “사물”로 인식하여 그것을 매개하며 공간에 배열하는 붓질을 신체 행위로 본다.[*로잘린드 크라우스, 윤난지 옮김, 『현대 조각의 흐름』, 예경, 1997, pp. 311-312 참고] 이때 박경률은 매우 비약적인 회화로의 변환을 감행하는 것처럼 보이는데, 그것은 사각의 모서리로 특정되는 회화의 공간에 대한 다차원적 전환이라 할 수 있다.

⟪환상 한 조각⟫에서는 전시 공간 전체를 150호(182x227cm/227x182cm) 캔버스가 여유롭게 채우고 있다. 각각의 캔버스 회화는 <Picture>라는 제목에 번호가 매겨 있고 괄호 안에 “in blue”라는 표기를 추가했다. 이와 같이 푸른 색조로 그려진 일련의 청색 회화에서, 그는 스푸마토(Sfumato)를 비롯한 대기원근법과 헬렌 프랑켄탈러(Helen Frankenthaler)의 얼룩 기법(Soak-Stain Technique)을 직접적인 레퍼런스로 가져와 고전적으로 푸른 색이 발휘해온 시각적 공간감에 한층 몰두했다. <Picture 94 (in blue)>(2021)와 <Picture 102 (in blue)>(2021)를 보면, 각각의 파란색 화면에 부유하고 있는 붓질의 흔적들이 (화면 내의) 주위를 살피며 시선을 계속해서 이동하도록 만든다. 하나는 대마(hemp)에 유화물감으로 그린 그림이고, 또 다른 하나는 황마(jute)에 그린 것이다. 박경률은 그림의 지지체로서 캔버스의 천을 중요하게 다룬다. 회화의 표면에 결정적인 영향을 주는 캔버스 천의 물성에 대해 그는 스스로 강렬하게 체감해 왔는데, 그것을 통해 또 한 번 회화의 공간을 실험하는 것이다. 요컨대, 그는 푸른 색 물감과 채색 기법과 캔버스의 물성을 조율해 가면서 일련의 다차원적 회화 공간의 가능성을 모색한 셈이다.

그가 조성해온 회화의 공간은 “전환”에 방점을 찍는다. 그것은 그가 말하는 그리기의 행위, 즉 붓질에서 시작되며 공간과 사물이 경험에 있어서 지각과 인식의 교차를 불러온다. 이를테면, 박경률은 회화의 평면 지지체로서 천의 물성과 직조 상태를 꼼꼼하게 살펴 붓질로 그 표면에 미세한 차이를 발생시킨다. 어떤 관점에서 받침대로부터 해방된 조각(적 사물)의 삼차원적인 배열과 흡사한 행위로서 박경률의 붓질에 대해 앞에서 언급했던 것처럼, 그는 스스로 조성한 회화 공간 안에 “오브제로서의 붓질”을 배열한다. 그것은 대마나 황마 같은 캔버스 천의 이차원적 표면에 놓이는 것이며, 동시에 천과 물감의 물성에 의해 실제 삼차원적 전환이 이루어질 테고, 게다가 그의 행위가 지닌 물리적인 힘과 기술에 의해 삼차원을 초과하는 비현실적 사유의 세계가 마치 (유령같은) 시각적 환영의 회귀처럼 새롭게 현전할 수 있게 된다. 이는 무척 논쟁적인 내용이지만, 마이클 프리드(Michael Fried)가 조명했던 미니멀리즘의 추상적이고 비지시적이며 실재하는 육면체 오브제들 표면 아래 (여전히) 잠재되어 있는 고대적인 인간 형상의 조각적 기원을 충분히 떠올리게 한다.

박경률의 조각적 회화는 일련의 삼차원 조각이 태생적으로 지니고 있는 지각과 인식 간의 간극 및 부조리를 일종의 방법론처럼 전유하는 망상이 엿보인다. 그리고 그것을 능숙하게 처리해낼 수 있는 회화 매체의 환영적 요소를 그는 다시 불러내, 조각의 차원을 매개하는 회화에 힘을 싣는다.

3.

이번 전시 ⟪환상 한 조각⟫에서 푸른 색의 <Picture> 연작은 박경률이 그동안 실험하며 모색해 온 조각적 회화의 여러 시도들 중에서 “환상”이라는 새로운 화두로 이어진다. 그는 이 전시에 대한 영문 제목으로 “fantavision”이라는 임의의 조어를 사용해 표기했는데, 그 단어에 내포되어 있는 요소들이 그의 조각적 회화에 대한 당위를 가늠케 한다. 그는 이 청색 회화에 대해서, “물성적 체험과 그에 따른 변환된 시공간의 마주침을 통해 예술은 사유를 강제하는 힘을 갖게 된다”고 했다.[*⟪환상 한 조각⟫에 대한 작가 노트 참고] 이 “마주침”과 “사유”는 환상으로서의 회화를 구축하는 중요한 개념으로 그에게서 다뤄진다. 여기서 나는 다시 한 번 하나의 조각적 사례로 미니멀리즘과 그 이후의 조각에 있어서 삼차원적 경험이 확인시켜 주었던 비가시성의 조각(적 환영)에 대한 사유를 가져와 보기로 한다.

<Picture 102 (in blue)>의 경우, 화면을 가만히 들여다 보면 붓질의 행위뿐 아니라 평면의 공간 안에 배열된 물감과 붓질의 제스처에 반응하는 캔버스 자체의 역동성도 가늠된다. 비어 있던 하나의 사각 캔버스에 원초적 행위로서 붓질이 오가는 동안, 캔버스는 제 몸체에 물감을 흐르게 하다가 멈추게 하고 쌓이면서 겹치게 한다. 이때, 박경률은 자신의 그리기 행위를 추적하듯 시각적으로 쫓으면서 동시에 이를 지속시킬 하나의 명분으로서 인식과 사유의 증폭을 꾀한다. 이를 위해, 그는 거친 붓의 덜 익숙함을 받아들이고 조색하지 않은 물감을 화면에 쌓아 올려 얼룩처럼 스미는 물성의 효과를 유도했다. 일련의 행위와 물성의 효과가 구축해낸 회화의 표면에는 실제적인 공간과 환영적인 공간이 교차하면서 “환상”으로서의 인식과 사유를 매개하게 된다.

그런 까닭에, “손으로 머리를 지탱하며, 시선에서 환상으로”라는 이 글의 부제는 조각적 경험과 인식을 통해 박경률의 회화로 진입하는 일련의 과정을 축약한 것이다. 알브레히트 뒤러(Albrecht-Düre)의 그 유명한 멜랑콜리아 포즈에서 손으로 머리를 지탱하고 있는 모습은 전형적인 비현실적 사유의 표상으로 다뤄진다. 날개 달린 여인의 시선은 현실의 사물들 앞에서 허공을 향해 있고 근본적으로는 어떤 비현실적 사유와 회의에 빠져있다. 내가 멜랑콜리에 빠진 인간의 몸을 생각했던 이유는, 아감벤의 철학적 사유에서 (불행한) 조각가가 가지고 있는 형상에 대한 실제적인 감각과 그것으로 인한 이미지에 대한 광적인 사랑/집착을 마치 하나의 동일한 사건처럼 떠올렸기 때문이다. 말하자면, 조각적 경험이란 조각가와 조각 사이의 대칭적 구조에서 실제적인 감각을 주고 받게 되어 있는데, 그것이 매우 물리적인 지각에 따르면서 동시에 비물질적 차원의 “인식”, 즉 대상에 대한 “앎”을 동반하고 있다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이 두 가지의 조각적 사건을 떠올릴 만한 개념으로 박경률은 “마주침”과 “사유”에 대해 말하고 있으며, 그것이 그가 이번 연작에서 유독 엄격하게 제한한 회화적 매체와 기법을 통해 차원의 변환을 거치면서 마침내는 회화의 (조각적) 조건에 대한 갱신을 가늠해 보게 한다.

1.

Artist Park Kyung Ryul, who has stated that painting is “fantasy,” repeatedly applies blue paint to enhance the immersiveness of her paintings. Without mixing colors, she places cerulean blue, manganese blue, and Prussian blue paint on the canvas, and she attempts to grant authority to the true nature of the paints confined within the grid of the painting (I wanted to use the term “repress,” but in order to avoid misinterpretation, I say “confined.”). In this context, when speaking about the materiality of the paint, the term materiality refers to both the paint’s existence as a readymade object from modernist avant-garde painting and as a form of matter that is both unique yet a purely chemical substance. Moreover, the artist grounds her work in a history of painting that has recognized the canvas as another three-dimensional substance, and she explores how she can allow the painting itself to exist as a material substance.

In the exhibition Fantavision, Park Kyung Ryul’s blue paintings offer an intense perceptual experience of color, and the inadvertent arrangement of the 150 canvases of identical size feels as if it is attempting to exclude the moment of narrative composition. Despite this, arbitrary shapes mediated by brushstrokes appear everywhere, with some shapes feeling rather familiar and others rather abstract and vague. Although this can be seen as producing a unique situation, in the concrete situation such as a painting exhibition, matter and objects as well as form and action tremble lightly, implying the possibility of transformation. Park Kyung Ryul employs the word “fantasy” to describe her work, and her paintings deal with several elements and attempt to affect a dimensional shift while keeping a firm grip on the (confident) hypothesis that these things can be given material form.

Park Kyung Ryul’s stance on painting—which employs arbitrary selection and judgement to recontextualize both discussions on modernist formalism, which guaranteed the autonomy of painting according to the purity of the medium, and discussions on modernist avenge-guard, which secured the autonomy of painting through everyday reference—is a form of declaration. Indeed, she states that “painting is fantasy.” This deeply meaningful declaration is a response to the question of whether painting, as a unique genre, still valid in our contemporary, image-centric society, and it begins from the artist’s recognition of the brushstroke as art object (form the Artist’s note for fanavision [2021]). It can be said that what she has concentrated on since the beginning is “brushstrokes,” which can said to be both an art object and action as well as a corps-pensée that mediates between multiple dimensions.

What Park Kyung Ryul refers to as “sculptural painting” is something that reveals her unchanging faith in painting, and, paradoxically, it also contributes to the renewal of the fundamental conditions of painting via a sculptural approach. While traveling back and forth across the bridge between painting and sculpture established in the previous century, she has avoided making the extension of the medium (as a thing) into a condition, and rather than focusing on painting as a three-dimensional, specific object, she has examined the distinctiveness of painting by employing “sculptural thinking” and a new understanding of medium. That is, during her work process, she confronts the tendency for three-dimensional perception of sculptural objects, which she has always emphasized, to find a final resting place in a pictorial form.

2.

What does the term “sculptural painting” mean for Park Kyung Ryul? She has stated, “The essence of sculptural painting can be found in an attention to ‘the act of drawing’” (Artist note for To Counterclockwise [2020]). Here, the sculptural approach to the act of drawing is reminiscent of the preoccupation with making sculptural attempts in three-dimensional theatricality after modernism, and this can be seen as an analogy for the bodily act of arranging particular objects within a physical space. Breaking away from the established environment of sculpture, when considering modernist attempts to experience the shape of “fact” through real materials in real space via the “use [of] edges and planes to shape an object,” it can be said that Park Kyung Ryul perceives paint and the canvas as one “material” and “substance” and views brushstrokes, which mediate between them and arrange them in space, as bodily acts (Rosalind E. Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture, The Viking Press, 1997, p. 266). Here, although Park Kyung Ryul appears to pursue the rapid transformation to painting, it can be said that this is a three-dimensional transformation of the pictorial space that is characterized by its four edges.

The Fantavision exhibition space is filled with canvasses that are either 182 cm x 227 cm or 227 cm x 182 cm. The title of each canvas contains the word “Picture” followed by a unique number and the parenthetical note “in blue.” Moreover, when applying the blue paints, the artist draws on the techniques of atmospheric perspective, including sfumato, as well as Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique to create a highly immersive sense of space. For example, in “Picture 94 (in Blue)” (2021) and “Picture 102 (in blue)” (2021), the traces of the brush on the blue plain of each painting encourage the viewer to scan their surroundings and continually refocus their gaze. One of the paintings is painted using oil paint on a hemp canvas, and another is painted on a jute canvas. Park Kyung Ryul places great importance on the fabric of the canvas as a support for the painting. She has an intense, physical sense of the properties of the canvas cloth, which she sees as having a decisive influence on the surface of the painting. Moreover, it is through this that she again experiments with the space of the painting. For example, she has experimented with the spatial potential of multi-dimension painting by balancing the use of blue paint, coloring techniques, and the materiality of the canvas. The space of the painting that she has created emphasizes “transformation.” It begins with what she calls the act of painting, or rather, the brushstroke, and it cause the perception and recognition of space and object to intersect. For example, Park Kyung Ryul meticulously examinees the properties and composition of the fabric as a flat support for the painting, and, through brushstrokes, she produces subtle differences on the surface. Similar to the discussion of Park Kyung Ryul’s brushstrokes, which constitute acts that are similar to the three-dimensional arrangement of sculptures that have been liberated from the display pedestal, she arranges the “brushstrokes as art objects” within the space of the painting that she has created herself. These brushstrokes are placed on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas fabric made of either hemp or jute, and, simultaneously, a three-dimensional transformation occurs due to the fabric and materiality of the paint. Moreover, due to the physical power and technique of her actions, an unrealistic world of thought that exceeds three dimensionality is brought into existence, like the return of a visual (ghost-like) illusion. Although highly controversial, it is reminiscent of the sculptural origin of the ancient human form that (still) lies dormant under the surface the abstract, invisible, non-directive, existing hexahedral object of minimalism that was highlighted by Michael Fried.

Park Kyung Ryul’s sculptural paintings relevel a delusional preoccupation (like a methodology) with appropriating the gaps and illogic between the perception and awareness that is inherent to three-dimensional sculptures. Moreover, she invokes the illusory elements of the medium of painting that can deftly deal with this, injecting her paintings, which mediate the dimension of sculpture, with power.

3.

Among the various sculptural paintings that Park Kyung Ryul has experimented with, this series of “Picture” paintings is of particular note, as it invokes the word “fantasy.” She coined the English-language title “Fantavision” for this exhibition, and the elements contained with the term make one consider the appropriateness of these sculptural painting. Regarding these blue paintings, the artist stated, “By providing material experiences and the resulting encounter with transformed time/space, art is endowed with the power to forcibly induce thought” (Artist’s note for Fantavision). For the artist, “encounter” and “thought” are central concepts that are instrumental to the construction of painting as fantasy. Here, I present non-visible sculpture (sculptural fantasy) as an example of a form of sculpture that reinforced three-dimensional experience in the context of minimalism and subsequent sculptural practice.

Looking closely at “Picture 102 (in blue),” one can observe not just the actions of the brushstroke, but also the dynamic response of the canvas itself to the gestures of the paint and brushstrokes that are arranged within the flat space of the canvas. As the brush strokes move in a primitive matter back and forth across the empty, square canvas, the canvas enables the paint to flow through the body, stop, and accumulate in layers. Here, as if tracing her own act of painting, artist Park Kyung Ryul chases it visually, and, simultaneously, as a pretext for sustaining this activity, she seeks to amplify awareness and thought.

For this purpose, she accepts the diminished familiarity of the brush while building layers of unmixed paint on the canvas to create the effect of a substance that has been smeared. In this painterly language, which is built from a series of actions and physical effects, real spaces and fantastical spaces intersect, mediating between thought and perception as “illusion.”

Therefore, the subtitle of this text, which reads “Supporting the Head with the Hands, from Looking to Illusion,” encapsulates the various process through which Park Kyung Ryul’s paintings have approached sculptural experience and perception. The image of a figure supporting their head with their hands in the famous melancholic pose depicted by painter Albrecht Dürer is treated as a representation of conventional, unrealistic thinking. The gaze of the winged women is directed at an empty space in front of real objects, and it is steeped in some sort of unrealistic thought and skepticism. I bring up the human body in a melancholic state because the realistic sense of the shape of the sculptor in Agamben’s philosophical thought and the fantastical love and obsession of the resulting image presented itself to me as if it were a unified event. That is, sculptural experience is something given and received within the mirrored structure existing between the sculptor and sculpture, and this both follows a very physical perception while also being a “perception” on a non-material level; that is, it is accompanied by a “knowledge” of the object. Park Kyung Ryul employs the terms “encounter” and “thinking” as words that gesture towards these two sculptural moments, and in this series of works, through a severely restricted painterly medium and technique, it undergoes a change in dimension, and, in the end, functions to interrogate the renewal of painterly (sculptural) conditions.

Exhibition Review:

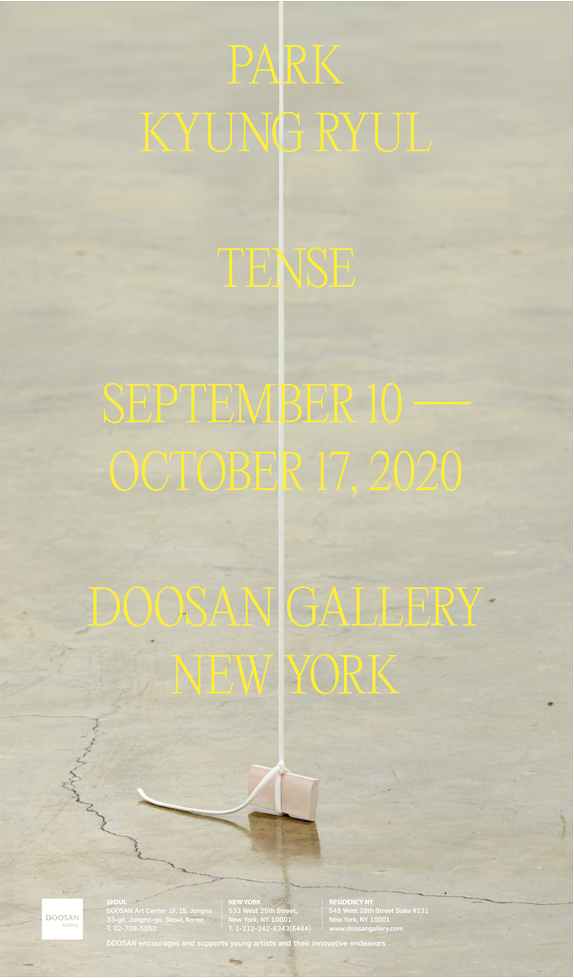

Park Kyung Ryul: Tense _ Jonathan Goodman (Poet and Art Writer), 2020

THE BROOKLYN RAIL OCT 2020

ARTSEEN: https://brooklynrail.org/2020/10/artseen/Park-Kyung-Ryul-Tense

Not quite a painting show, not quite a show of sculpture, not quite a show embodying an installation, Korean artist Park Kyung Ryul’s Tense is taut with possibility. Developed from her residency at the DOOSAN Gallery, Park’s sophisticated show seeks to expand the flatness of painting to a three-dimensional degree. There are a couple of actual paintings set against the wall in the L-shaped gallery space, but Tense also creates an installation space filled with such elements as ceramics, sculptures, and objects in addition to the paintings mentioned. Park has produced a rather theoretical statement for her audience to read, but the work is not so dense as to justify excessively abstract thought. Instead, it witnesses an intelligent artist’s wish to explore how form occurs and how the genres of painting, sculpture, and installation may be effectively joined. The show is inherently contemplative, in the sense that it takes time to traverse the materials of the exhibition, which mostly lie on the floor. The many components of Tense, which include odd objects, wooden dowels, and small abstract ceramic sculptures, can be likened to Park’s personal dictionary of forms, which communicate, both singly and as a group, the infinite possibilities of a loose arrangement of eccentric materials.

Even though press materials claim the show is an attempt to expand the structure of paintings, it is hard not to see this work as a collection of sculpture, embellished by a few colorful, abstract two-dimensional works. They seem to be deliberately placed and randomly arranged in the same moment, expanding the visual idiom of the installation in ways that correspond to abstract art, both painting and sculpture. The presence of these discrete objects is close to arbitrary, in the sense that we don’t know fully why they exist where they are. Yet, at the same time, it is clear that an overriding intelligence on Park’s part is evident. As one walks down the long corridor of the space, it becomes necessary to pass among the elements without touching them. So the viewer becomes an active participant in the show, fulfilling its implications—both remaining physically tense and proceeding purposefully—by movement. The pieces on the floor are too various and too numerous to easily describe, but it can be said that they remain mostly flat on the floor, so that the field itself becomes a kind of background to a low relief. Thus, we are looking downward for an explanation of the painting genre, which we associate with being mounted on the wall. It is a deliberate destabilization of our expectations, one which expands the possibilities of the painterly fields.

As for the paintings themselves, they are at the end of the corridor and do not necessarily assert themselves as a major focus of interest. Instead, they are part of Park’s larger view, in which individual objects assemble in ways that cohere into a recognizable pattern or scheme. One oil painting, Picture 11 (2019), is mostly yellow, decorated with unrecognizable blue, green, and red organic shapes and contour lines that come close to graffiti. Another work, Picture 12 (2020), has a light background, on top of which we find doodles and informal abstract shapes: yellow lozenges with black markings, linear squiggles, forms beyond description. Irregularly formed ceramic tubes—almost like bones—are arrayed on the floor before the painting, one propped against the wall directly under the canvas as if to offer support.

These paintings may not be completely effective as works in their own right, but they contribute well to the general metaphysics of the show, which seeks to deconstruct the image into components that litter the gallery in an attempt to introduce random creativity into what is usually considered a conscious operation. Park’s theory, a bit difficult to understand in her dense artist’s statement, is abundantly clear in her art. She is leading us in a direction of philosophical inquiry, although her tools are not linguistic but visual. This is a good thing, because her ideas become secondary to the impulse of her hand and eye. In this way, Park is pushing our investigations forward, into a place where a philosophy of form is enacted, but in visual ways that keep any dominance of an idea at bay. Recognition of the work of earlier artists, such as Mel Bochner, Robert Morris, and Eva Hesse, allows us to see the work in context, but one has the sense that Park has mostly created the show according to her own creative design. Her independence of thought is paramount, which means that she is effectively communicating a contemporary point of view—but one that can be understood as a maverick expression. This carries weight in a time of often unimaginative, conventional art.

비계층적 회화 And another criterion[1]

박경률 개인전: 왼쪽회화전_신지현 (독립기획자), 2020

“Non-hierarchical picture”

Park Kyung Ryul’s Solo Exhibition To Counterclockwise

Shin Jihyun (Independent Curator), 2020

비계층적 회화(non-hierarchic picture)”

장구한 역사를 가진 매체 회화는 언제나 평면 안에 혹은 그 자체로 존재해 왔다. 그리고 오늘날 많은 페인터들은 오래된 매체를 딛고 미래로 나아가기 위한 시도를 여전히 지속하고 있다. 일견 전형적인 회화 안에 머무는 듯 보이지만 회화적 통일성과 극적인 구성을 추구하는 전통적 미술의 목표는 물론, 로저 프라이(Roger Fry)와 클라이브 벨(Cliv Bell)이 높게 평가했던 “의미 있는 형식”이나 클레멘트 그린버그가 최종 목표라고 설파했던 “평면성”[2]으로부터도 벗어나 있는 박경률의 그림을 우리는 어떻게 읽어야 할까? “회화를 회화적이게 만드는 규율을 하나씩 거두어나간 과정”이라는 그의 말이 흥미로운 것은 회화로부터 도망친 자리가 여전히 회화적이기 때문이다. 이 그림을 온당히 읽어낼 수 있는 새로운 규준이 필요하지 않을까? 또 다른 규준(another criterion)이 필요한 순간이다.

박경률의 회화를 “비계층적 회화(non-hierarchic picture)”라 불러보고자 한다. 붓과 캔버스를 손에 쥔 채 모종의 회화적 실험을 지속 중인 그의 작업 전반에서 비계층성은 꾸준히 포착되어 왔다. 초기작부터 이야기하자면 꽤 치밀한 묘법으로 형상을 그리면서도 으레 회화에 기대하는 내러티브가 없는, ‘탈내러티브적 구상회화’(2012-2008)를 통해 ‘오브제로서의 붓질(piece of brush stroke)’을 감행한 바 있으며, 가깝게는 직전의 개인전 «On Evenness»(2019, 백아트 서울)를 통해 캔버스로부터 도주한 오브제들이 도열한, 일종의 회화적 공간을 구축해 내며 회화를 회화적이게 만들기 위해 따라붙어온 관습적 요소와 질서들—색, 선, 구도, 형상, 내러티브, 정신성 등—을 제거해 나아가는 과정에 있어 왔다. 그의 그림 속 회화적 요소들은 그 어떤 위계나 상호 연관성을 갖고 있지 않은 채 각각 독립적 개체로서 존재할 뿐이다. 이러한 비계층적 태도는 이번 전시 «왼쪽회화전»에서 선보이고 있는 작품의 제목에서도 예외가 아닌데, <그림 1>, <그림 2>와 같은 제목은 <untitled>의 그것과는 또 다른 것으로, 제목없음이 아닌 일반명사 그 자체가 대상을 호명하는 고유명사가 된다. 아무런 의미를 안 담고 있지는 않으면서도, 그렇다고 큰 의미를 담고 있지도 않은 익명의 오브제와 같은 제목이자 박경률의 회화적 태도를 가늠할 수 있는 대목이 되겠다.

어떤 것을 재현(representation)하지 않는 그의 화면엔 총체성이 없고, 그렇기에 가볍게 전통적 회화의 관습을 비껴간다. 모든 것이 평등한 그림의 상태(pictorial field)를 유지하고 있는 그의 회화는 다시 말해 아무것도 특별히 가리키지도 의미하지도 않는다. 그 자체일 뿐. 그에게 중요한 것은 캔버스를 마주했을 때의 상황에서 발생하는 운동성으로서의 붓질, 그리고 그림이 공간에 걸림으로써 만들어지는 사건(event)으로서의 전시이다. 그에게 캔버스는 그저 “얕은 공간”이며 전시장은 “깊은 공간”에 지나지 않는다. 그리고 여기에서 모더니즘의 절대성을 다시 한번 벗어난다. 이번 전시 «왼쪽 회화전»에서는 그가 진행해온 회화적 실험을 지속하면서도 ‘캔버스 안’으로 공간을 제한하기를 시도한다.

“선적인 것에서 면적인 것으로”

안료를 얹고 덮는 작업을 통해 기본적인 면을 이루어내는 전통적 회화에서 선은 눈의 궤도이자 지침으로써 촉각적으로 수용되는, 즉 윤곽선으로서 의미를 가져왔다.[3] 여기에서의 선은 형상의 명료한 재현을 위한 것이라 하겠다. 그리고 모더니스트 회화는 지각 가능한 3차원 물체가 담길 수 있는 공간에의 재현을 포기해 버림으로써 절대 평면성 그 자체를 회화의 독자적 요소로 간주하기에 이르른다. 일반적으로 전통적 회화를 볼 때 ‘그 안에 무엇이 그려져 있는가’를 먼저 보았다면 모더니스트 회화의 경우 무엇보다도 ‘하나의 평면 그 자체’를 먼저 보는 것이다.[4] 그러나 박경률의 회화는 이 둘의 독해법을 모두 비끼며, 2차원 평면이 가질 수 있는 공간성에 관심을 가지면서 동시에 그 어떤 형상도 재현하지 않는 면모를 보이기 시작한다.

«왼쪽 회화전»에서 선보이는 12개의 <그림> 시리즈에서는 독립적이고도 조각적으로 존재해온 선들이 본격 그 형태의 한계가 분명하지 않은, 보다 회화적인 상태로 변화하는 모습이 포착된다. 선적인 것에서 면적인 것으로의 이행이라 하겠다. 그리고 작가는 언제나 그렇듯, 이를 선형적 흐름으로 전시장에 놓는 것이 아닌 리드미컬한 배치를 통해 보는 이로 하여금 이리저리 돌아보게 만들어 조각적 회화에서 회화적 회화로의 변화를 탐구자의 시선으로 좇아내게 한다. 이전보다 레이어와 형상이 줄어든 <그림> 시리즈를 구성하는 것을 크게 선과 색이라고 본다면, 여기에서의 선의 역할은 형태의 테두리를 위한, 즉 촉각적 모델링으로서의 그것이라기보다는 하나의 독립된 형(形)이자 본능적으로 나오는 신체감각의 흔적으로서의 선이며, 색은 ‘얹히는’ 대신 ‘스미는’ 방식을 통해 면과 일체화되는 동시에 면이 담지한 깊이감을 회화적으로 드러내길 시도하는 그라운드로서 존재한다. 그렇기에 오롯한 평면만을 남겨둔 이 전시는 일견 전형적 회화로의 복귀처럼 보일 수 있지만, 정확히 이야기하자면 복귀 아닌 다음 장이며 캔버스라는 ‘그라운드’가 담지하는 공간에의 관심, 깊이감에의 실험이라 할 수 있겠다. 그리고 여기에는 밑작업(foundation)을 최소화하고 회화의 재료로서 면천의 종류와 그에 따른 두께, 짜임 방식은 물론 물감 사용법과 작가의 움직임까지도 바로 전에 그린 그림과는 다르게 하는 매질 실험이 전제된다. 이 과정에서 발생하는 회화적 요소 간의 교차와 충돌은 서로 다른 구도와 맥락을 형성해 내기도 하는데, 이는 작가도 예측할 수 없는 범위의 일로 이 이후엔 그림 앞에 서 있던 주체로서의 작가의 존재마저도 희미해진 채 작업은 스스로 발화하는 단계로 접어든다고 볼 수 있겠다.

“눈으로 걸어 다니기”

다시 질문. 전통적인 것을 고수하면서도 그에 따라붙은 관념적인 것을 해체하려는 시도, 그리고 이로부터 확장된 회화 읽기를 시도하는 박경률의 회화를 우리는 어떻게 바라보아야 하는가? 회화를 재현의 매체 혹은 완결의 매체가 아닌 그라운드 위에 물감이 닿는 순간부터 전시장에 놓이는 지금까지 지속되고있는 수행의 매체로 바라보는 박경률의 태도는 회화를 여전히 현재 진행형이게 만든다. 우리는 가까이에서 멀리서, 또 낮은 곳에서, 높은 곳에서 캔버스 너머의 공간을 바라보고, 그 안의 “아무것도 재현하지 않는 형상적 이미지”, 붓질 오브제 사이를 그저 눈으로 걸어 다니면 될 일이다. 이 관람의 경험을 끝내고 전시장 문을 닫고 나감으로써 작품은 비로소 완결된다. 그렇다면 이 화면이 창출해내는 새로운 규준이란 과연 무엇인가? 그것은 작품을 전시장에서 마주하는 행위, 그 ‘사건’을 경험함으로써 변화하기 시작한 사람들이 회화를 읽어내는 방식이며, 이 변화로부터 그의 작품은 이미 또 다른 규준(another criterion)을 생성해내기 시작했다고 볼 수도 있지 않을까?

[1]. 이 글의 제목은 레오 스타인버그(Leo Steinberg)가 쓴 책의 제목 『Other Criteria』에서 차용한 것임을 밝힙니다.

[2]. 할 포스터·로잘린드 크라우스 외, 배수희·신정훈 외 옮김, 『Art Since 1990-1900년 이후의 미술사』(세미콜론, 2007), 517쪽.

[3]. 하인리히 뵐플린, 박지형 옮김, 『미술사의 기초 개념: 근세미술에 있어서의 양식발전의 문제』(시공아트, 1994), 32, 71쪽.

[4]. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Art and Literature, no.4, Spring 1965, pp. 193-201.

“Non-hierarchic picture”

Throughout its long history as an art form, paintings have existed either in the flat surface or as the flat surface itself. Today, many painters continue the effort to forge a future for this archaic medium. At a glance, Park Kyung Ryul’s paintings may appear to bide within the framework of conventional paintings. While Park’s works indeed accomplish the objectives of traditional art in ensuring painterly unity and dramatic composition, they also veer away from the “meaningful form” that Roger Fry and Clive Bell so lauded and from the “flatness” [1] that Clement Greenberg evangelized as the final goal of paintings. How then, should we interpret such works by Park? Park’s description of her art as “a process of shedding the conventions that make paintings painterly, one at a time” is interesting, as her flight from the painterliness remains ever painterly. Perhaps this raises the need for a new set of criteria that can interpret works like Park’s. Indeed, the moment calls for “another criterion” for examining paintings.

For the purpose of this writing, I will dub Park’s paintings as “non-hierarchic picture.” Non-hierarchy has been consistently spotted in Park’s works as she continued her painterly experiments with her brush and canvas. In her early works, Park employed elaborate tactics to paint her forms while omitting the narrative duly expected of paintings. Through such “post-narrative figurative paintings” (2012-2018), Park attempted to create a “piece of brushstroke”. In her more recent solo exhibition On Evenness (2019, Baik Art Seoul), Park presented objets that fled from the canvas and lined up to establish a sort of a painterly space. Park then has been removing each conventional elements and orders that make paintings painterly, such as colors, lines, composition, form, narrative, and spirituality. Each painterly element in Park’s works exists as an independent entity without any hierarchical or mutual affiliation with the others. Such non-hierarchical attitude can be seen in the titles of the works featured in the current exhibition, To Counterclockwise. For instance, titles like Picture 1 and Picture 2 are different than a title like untitled as the common noun used herein becomes the pronoun to refer to the painting. Such titles bear some meaning while also not bearing any overly significant meaning, much like the titles for anonymous objets. This provides insight on Park’s painterly attitude.

Not a representation of anything, Park’s painting is devoid of totality, which enables it to effortlessly graze past the conventions of traditional paintings. With every element maintaining an equal level of pictorial field, Park’s paintings do not indicate or signify anything in particular. They’re just what they are. What is important to Park is the kinetic movement of the brushstrokes against the canvas and the exhibition as an event manifested by the gesture of hanging the paintings in the exhibition space. To Park, a canvas is merely a “shallow space,” just as the exhibition space is a “deeper space.” Here, Park drifts yet again from the absoluteness of modernism. In To Counterclockwise, Park continues her painterly experimentation while also attempting to limit the space to “within the canvas.”

“From linear to planar”

In traditional paintings that create basic planes by stacking coat after coat of paint on the canvas, lines provided the trajectories and reference points for the eyes, i.e. bringing meaning as tangible outlines for the viewer.[2] For the purpose of this explanation, let us say the objective of lines is to provide a clear representation of form. Modernist paintings forfeited the representation of perceptible three-dimensional objects in the given space, thereby assuming absolute flatness itself as an independent factor of paintings. Normally, traditional paintings presented something “within the painting” as the main subject, whereas modernist paintings presented “the flat surface itself”.[3] However, Park’s paintings are not aligned with either of such conventions. Instead, they show interest in the spatiality of two-dimensional planes while also refusing to represent any forms.

The 12-piece Pictures series in To Counterclockwise feature lines that have existed independently and sculpturally begin to shift into more painterly forms without clear limitations. This is characterized as the transition from the linear to the planar. As always, Park places her works rhythmically instead of opting for a linear flow, thereby leading the viewer to inspect every nook and cranny and encouraging the viewer to discover the transformation from sculptural paintings to painterly paintings. With less layers and forms than before, the Pictures series is largely comprised of lines and color. Here, the role of the lines is to serve as an independent form and traces of instinctive physical sensation, rather than provide the tactile model for the outlines of the form. Color becomes something that “seeps”, rather than “coats”, becoming one with the plane while serving as the ground that attempts to unveil, in a painterly manner, the depth inherent in the planes. As such, while this exhibition may appear to be a return to the traditional painting solely comprised of planes at a glance, it’s more of a progression to the next chapter instead of a retrograde movement. The exhibition is the manifestation of the interest in the space inherent in the “ground” or the canvas, and an experiment on depth. A premise for such efforts is the experimentation with the medium, such as minimizing the foundation, and using canvases of various materials, thickness and weaving, and varying the use of paint and the physical movement of the artist. The intersection and collision of the various painterly elements in this process creates varying compositions and context, which even Park cannot fully predict. After this, even the existence of the artist as the creator grows faint as the work enters the phase of speaking for itself.

“Walking with the eyes”

This brings us back to the question: how should we perceive Park’s works as she insists on the traditional while also attempting to dismantle the conventions that follow, and exerting efforts to interpret the ensuing extension of painterliness? Park sees painting, not as a medium of representation or completion but as a performative medium which continues from the moment paint is applied to a certain ground, to the present moment of it being placed in the exhibition space. Such outlook on painting makes it something present-progressive. All we can do is look at the space beyond the canvas, standing somewhere near it, or perhaps below it or above it, and tread between the brushworks or the “images of form that do not represent anything”. The work finally becomes complete when we end this experience by exiting the gallery. So then perhaps we can say that another criterion generated by Parks’ work is a way of reading the painting through the gesture of confronting the work in the exhibition space, and through the transformative experience of such ‘happening’.

[1] Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss et. al, Art Since 1900, trans. Bae Suhee and Shin Junghoon, (Semicolon, 2007), 517.

[2] Heinrich Wölfflin, Kunstgeschichtlichee Grundbegriffe, trans. Park Ji-hyung, (Sigong Art, 1994), 32, 71.

[3] Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Art and Literature, no.4, Spring 1965, pp. 193-201.

다시 감각으로의 회귀 : 감각을 그리는 방식_신지현 (독립기획자), 2019

For you who do not listen to me _ Oil on canvas, acrylic sheet, sunlight _ Dimensions variable _ Baik Art Seoul Gallery _ 2019

오후 세 시에 비로소 완성되는 회화

작품을 처음 본 순간을 생각해본다. 당시 전시장을 메우고 있던 수십, 수백 개의 오브제보다 이 하나의 작품, 설치, 그리고 공간이 나에겐 가장 반짝이고도 아름답게 다가왔다. 오후 세 시 전시장의 커다란 창 너머로 쏟아지는 빛을 가장 인공적인, 그 어떤 미적 감각을 보유하기는커녕 표준값에 근거한 계산에 의해 조색된 공산품이 만들어낸 파랑색에 투과 시켜 고심해서 골랐을 작품의 컬러를 이상하게 만들어버리고 마는, 그리고 그제서야 작품을 완성시키는 균형의 감각에 대한 이야기. 박경률 작가의 회화에 대해 조금은 더 이야기 할 수 있을 것 같았다.

이야기에 대한 무관심, 비서사적 구조

초기작을 먼저 살펴보자. 세밀한 묘사가 돋보이던 2012-2008년도 작업은 작가의 머릿속일까 거대 서사를 품은 소설일까 복잡한 상상의 단초를 제공한다. 무수히 떠다니는 도상을 부감으로 바라보는 풍경은 불현듯 유토피아를 가장한 디스토피아를 연상케 하기도 한다. 이미 언어화된 사물들은 의미로부터 자유로울 수 없고, “사람을 괴롭히는 것은 사물 자체가 아니라 사물에 대한 사람들의 생각이다”[1]라는 말처럼, 그림 속 도상에 따라붙은 관념은 어느새 내러티브가 되어 유령처럼 우리를 지독히 따라다닌다. 그러나 리코더와 땋은 머리, 수탉과 회전목마, 마작과 아그리파가 도대체 무슨 이야기를 만들어낼 수 있을까? 짐짓 알레고리 가득한 모양새를 하고 있지만 그 어떤 코드도 읽어낼 수 없기에 우리는 그저 ‘감각’하는 단계에 머물 수 밖에 없다. 스토리는 없지만 등장인물만 가득한 소설 같은 박경률의 회화를 바라보며 멈칫하는 순간이다.

초기작의 치밀한 묘법마저 근작으로 넘어올수록 스스로 추상화하는 동태로 변모하는 것이 눈에 띈다. 2017년을 기점으로 관찰되는 시각적 변화는 불필요한 선과 묘사를 덜어내 보다 감각에의 집중을 호출하고, 형태를 비워낸 자리엔 색과 붓질을 채워 넣었다. 이 수수께끼 같은 회화에 대해 작가는 직관적으로 나오는 제스처라고 말할 뿐이다. 그린다는 행위에 대해 머릿속을 빠르게 지나가는 생각 혹은 미처 언어화되지 못한 감각을 붙잡으려는 시도라 이야기하는 작가는 그렇게 ‘캔버스’라는 물질을 지지체 삼아 그 위에 ‘물감’이라는 물성이 얹어 ‘붓’을 쥔 몸이 담지하는 운동성에 의해 순간을 기록해나간다. 좀 더 엄밀히 이야기하자면 ‘기록’한다기보다는 ‘배치’하는 것에 더 가까운 회화라 하는 것이 적당하겠다. 캔버스라는 무대 위에서 다양한 구조를 이루고 있는 이미지들은 총체적 조감도라기보단 개별자의 군상이며, 시간성에 기반해 선형적으로 흐르는 서사의 배치가 아닌 독립적으로 그려진 '이미지-조각'(piece of brush stroke)들이라 할 수 있기 때문이다. 그렇기에 하나의 표면 위에 집적된 다양한 이미지가 어떤 이야기를 상상하게 하는 것은 당연하지만 아무런 이야기도 품고 있지 않는 것 또한 당연하다. 직선을 곡선으로 만들고 곡선을 토막 쳐 우연과 농담, 신비와 환상, 확신과 불확정성의 유희를 오가며 비서사적 구조를 이루어내는 데에 충실하던 화면은 마침내 캔버스를 넘어 공간으로의 포월(匍越)을 시도한다.

무대를 휘젓는 감각

런던 유학 시절 사이드룸(SIDE ROOM)에서의 전시 《New Paintings》(2017)를 기점으로 작가는 회화라는 매체를 다루는 데에 있어서 ‘화면’이라는 제약에서 벗어나는 듯 보인다. 이후 국내에서는 2018년 송은아트스페이스에서의 전시를 통해 본격적으로 캔버스로부터의 도주가 가시화되기 시작한다. 공간에 놓여있는 무명의 수많은 '사물-조각'(piece of object)들을 보고 있자니 ‘새롭다’기보다는 ‘자유로워졌다’는 표현이 더 적절해 보인다. 이것들은 다름 아닌 그간 하나의 표면 위에서 붓질로써 해결 보아왔던 '이미지-조각'의 현현에 다름 아니기 때문이다. 표면을 벗어나 공간으로 확장된 사물들은 그의 평면 속 도상과 마찬가지로 특정 연관성에 기인하지 않는다. 파운드 오브제가 아닌 우연히, 자연스레 선택된 사물 한 조각이 툭 던져진 그 자리가 제자리이면서 굳이 그 자리에서 살짝 빗겨나가도 틀리지 않는 그의 계산법. 작가가 매체를 다루고 구조를 이루는 방식은 여전히 그대로인 것 같다. 각각 독립적으로 존재하는 사물이 쌓아 올려진 순서를 상상하며 이제 우리의 시선은 그가 지휘하는 무대(그것이 종이든, 캔버스든, 전시공간이든)를 휘젓는 감각으로 확장된다. 전시장에 들어온 관람객은 필연적으로 그림과 사물 사이 앞과 뒤를 오가며 각자의 리듬으로 고유의 동선을 만든다. 관람자 개개인의 특이성과 우연성에 따라 생성되는 스코어는 박경률의 작업 방식과 같이 자연스럽고도 개별적이다. 그렇게 공간에 각자가 남기고 사라진 감각의 흔적, 관람의 기록은 마치 무보(舞譜)와 같다. 박경률 작가의 작업은 그렇게 가장 물질적인 매체를 쥐고 가장 비물질적인 순간을 향해 나아간다.

다시 감각으로의 회귀 : 감각을 기록하는 방식

공간과 움직임, 시간과 리듬에 의거한 납작하고 작고 가벼운 것들이 서로를 기대고 지지하며 균형을 이루어 서 있다. 회화가 과거, 그러니까 붓을 들었던 그때의 시간성을 고스란히 보유한 매체라면, 박경률 작가는 그 시간성을 현재로 끌어와 공간으로 확장시켜 여전히 현재 진행형이게 만든다. 평면에 그리고 공간에 가만히 놓여있는 그것들은 관람객을 스스로 움직이게 한다. 어긋남과 맞물림 사이를 오가며 오브제를 겹쳐 쌓았을 작가의 수행을 상상하게 하는 한편, 파편처럼 흩어져 연출된 무대의 풍경을 감각하길 열망하게 만든다. 자신의 작업은 색, 형태, 구성 등 그림을 그림이게 만드는 경계와 제약을 거두어 나가는 과정이라고 말하는 작가에게 현존의 매체 회화가 공간으로 나아가 보이지 않는 어느 지점에 가닿는 순간 완성되는 것이라면, 그 완성의 지점은 어디일까? 물질과 비물질 사이를 돌고 돌아 2D가 3D가 되었다가 다시 2D로 환원하는 과정에서 획득되는 고유의 순간 같은 것 말이다. 그 끝을 결정지워주는 것은 예측 불가능성, 그리하여 우연성이 자연스레 개입하는 각자의 어떤 순간, 이를테면 오후 세 시 작품에 빛이 반짝 비추는 그런 순간이지 않을까?

[1]. 로렌스 스턴. 『신사 트리스트럼 섄디의인생과 생각 이야기』, 을유문화사, 2012, p. 6.

* 인천아트플랫폼 레지던시 비평 프로그램(2019) 일환으로 작성된 글입니다.

Returning to the Senses: Ways of Drawing_SHIN JiHyun (Independent Curator), 2019

The painting finally completed at 3 p.m.

I look back at the first time I saw this work. This single work, installation, and space shined more brightly and beautifully for me than the dozens, hundreds of objects that filled the exhibition space at the time. This is the story of a work that projects the 3 p.m. sunshine blazing through the exhibition space’s window onto an artificially mass-produced object based on standardized values, thereby rendering eerie coloration in the work, seemingly void of any aesthetic taste. Yet the colors are so uncanny that they bring the work a sense of completion and balance. This is the story of PARK Kyungryul’s paintings, which I believe I can now elaborate on a bit further.

Disinterest in the story; a non-narrative structure

Let’s begin by looking at the artist’s earliest works. Featuring meticulous details, her works from 2008 to 2012 hint at complex imaginations taking place in her mind, perhaps like an epic novel. The high-angle view of the countless icons floating about evokes an image of a dystopia pretending to be a utopia. Objects already codified into language cannot become free from meaning. Like the saying “objects do not harass people; it is the people’s thoughts about the objects that harass them,”1) the concepts already adhered to the icons in painting quickly become narratives that tirelessly haunt us like ghosts. However, how can a recorder, braided hair, cock, merry-go-round, mahjong, and Agrippa possibly weave a story together? While the scene is ostensibly filled with allegories, it remains impossible to decipher any particular code, leaving the audience at merely “sensing” the work and nothing more. Like a novel filled with characters without a real story to follow, the artist’s painting forces the viewer to flinch and pause.

PARK Kyungryul’s meticulous details noticeably become more abstract in her later works. Such visual change can be found starting with her works from 2017. She removed unnecessary lines and detailing, requiring greater focus of the senses when appreciating her work. In the spots that no longer sport the detailed forms which the artist would have placed in her earlier works, the artist fills the gap with color and brushwork. She merely addresses such mysterious painting as a result of intuitive gestures. The artist calls these gestures an attempt to grasp the thoughts that quickly cross the mind when engaging in the behavior known as “painting” or the senses that have yet to become codified in language. Thus on the material called “canvas” as the scaffold, the artist records the kinetic movements of the body-gripping the brush coated with the materiality of the “paint.” To be more precise, her painting can be better described as an act of “emplacement” than “recording.” The images that comprise various structures atop the stage of the canvas are more like a group of individuals rather than a collective whole that renders the bigger picture. These images are not placed to create a temporally linear narrative, but rather serve as independently placed “pieces of brushstrokes.” Therefore, while it may seem natural to expect that various images stacked atop a common surface would provoke the imagination of a story, it may also be natural that they do not, in fact, contain any story whatsoever. The artist canvases turn straight lines into curves, which are then chopped up to hop around playfully between coincidence and jest, mystery and fantasy, and certainty and uncertainty. The surface of this works thus remains faithful to creating a non-narrative structure until it finally attempts to transcend into the space beyond the canvas.

The sensibility that sweeps the stage

During her studies in London, she held the exhibition New Paintings (2017) at the SIDE ROOM. It was at this point that the artist appears to begin freeing himself from the shackles of the “surface” when dealing with the medium of paintings. Later in Korea, her flight from the canvas began to become fully apparent in her exhibition at the Songeun Art Space in 2018. The many unnamed “pieces of objects” placed in the exhibition space could be more appropriately described as “free” than “new.” This is because such objects are in fact the physical manifestations of the “pieces of images” she previously sought to portray through her brushstrokes on canvas.

Expanding into physical space beyond the flat surface, her subjects do not find their basis on specific relationships much like their counterparts on canvas. They are not found objects, but rather something that the artist just happened to select naturally. While these objects are seemingly placed in a disinterested way, each of their position feels like their own. Yet at the same time, a slight shift from their established position does not feel so wrong either, per her deliberate calculations. The way she deals with her materials and forms structure appears consistent with her previous methods.

As we imagine the order in which the artist stacks each independent object, our gaze is drawn to the stage conducted by the artist (whether that is on paper, canvas, or exhibition spaces), expanding our senses. The audience who enters the exhibition space inevitably weave through the paintings and objects, thereby creating their unique lines of movement at their own pace and rhythm. This “score” generated by each individual’s particular traits and simple coincidence is as natural and distinct from each other as her method of working. Such traces of senses and audience left behind by each viewer resemble a dance score. Her works thus grasp the most physical medium as they head towards the most immaterial moment.

Return to the senses: Recording sensations

The flat, small, and light things based on space, movement, time, and rhythm rely on each other, supporting each other to create a balance. If paintings serve as a medium that preserves the temporality of the very moment the brush was held in the painter’s hand, the artist strives to bring such temporality to the present and expand it into space, turning it into the present form. The elements sitting still within the canvas or in the actual physical space prompt the audience to move. As the audience weaves through the jagged gaps between the works, they are encouraged to imagine how the artist stacked the objects and yearn to take in the sight of the stage presented like a dispersed collection of fragments. the artist refers to her works as a process for removing the boundaries and limitations that define a painting, such as color, form, and composition. If she considers that the paintings of present become fully complete when they reach a certain point in physical space, where then, does that point of completion lie? Perhaps it is unique moment that can be found amidst the endless cycling between the material and immaterial, wherein the two-dimensional becomes three-dimensional only to retrograde to two-dimensionality again. Perhaps the decisive factor that determines the point of destination is unpredictability, a certain moment when coincidence intervenes, when the afternoon sunshine briefly reflects off the work at 3 pm, for example.

1) Sterne, Lurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Eulyoo Publishing, 2012, p. 6.

* This manuscript was written as part of Incheon Art Platform Artist-in-Residence - criticism program (2019)

Exhibition Review ; On “ON EVENNESS”_조주리 (독립기획자), 2019

연일 특색있는 회화 작업들을, 기세있게 쏟아내는 박경률의 퍼포먼스를 지켜보는 일은 그만큼이나 신이난다. 그가 꼭 박경률이어서가 아니라, 그로부터 비슷한 세대의 페인팅 작가들이 품어왔을 고민과 내파, 복구와 재건에 이르는 과정 속의 실험과 성장의 징후들을 투영해 볼 수 있기 때문이다. 시기적으로 현재 백아트에서 열리고 있는 개인전 <On Evenness>는 최근 몇년간 부단한 실험을 통해 스스로가 견인해 온 도약의 지점에 와 있는 프레젠테이션이다. 미술계에서 반복되어 온, 회화의 회화성을 둘러싼 재귀적 담론이나 세대론의 프레임에 자기작업의 특수성을 녹여내는 일에 큰 흥미가 없어 보이는 작가에게 스스로의 작업논리와 창작리듬은 어떤 것이 선재先在하기 보다는 서로 밀고끌며 회화적 실험의 모멘텀을 만들어 가는 힘이다.

세 개의 층을 따라 분할된 공간에서 마흔 점 이상의 회화와 조각, 세라믹, 오브제들이 여러 집합과 분산을 이루어 내는 전시의 솔루션은 “회화로부터 확장된 복합설치”의 방식으로 서술될 수 있다. 그러나 회화 개념과 실천의 측면에서 여러 키워드를 관통하는 이번 전시는 퍽 기이한, 경우에 따라서 난해한 풍경이다.

전시는 작년 송은아트스페이스에서 선보였던 “조각적 회화 설치”의 디스플레이 전략과 특유의 색채사용에서 비롯된 무드를 잇고 있지만 현장에서 체감하기에 이전보다 훨씬 정치하게 설계된 우연과 무연의 질서가 있다. 건축의 수직적 입면과 층을 달리하며 조금씩 바뀌는 평면적 조건에 반응하며 걸리고 놓인, 때에 따라 깔리거나 매달려있기도 한 작품들은 카메라 앵글과 관람객의 망막 상에서 높이와 크기, 중첩된 면적과 각도를 매번 달리 제공한다.이러한 전시의 미장센은 관람객들로 하여금 작품을 단독적 대상으로써 감상하는 것을 훼방한다. 그리고 전시에서 무엇인가를 보았다는 미적 충족감을 쉽게 내주지 않는다. 결과적으로 전시장에 머무르는 시간을 지연시키며, 자꾸만 지나온 자리를 되 살피게 하는 것은 작품의 열린 구조 때문이기도 하다. 화면을 구성하는 정형과 비정형, 추상과 구상, 실재와 상상의 파편들 간의 기묘한 어긋남/어울림은 이내 화면 외부로 확장되어 전시장 안팎에서 일종의 프랙탈 구조를 이룬다. 다종의 것들이 특히 더욱 조밀하게 몰려있는 2층 공간에 이르러, 관람객의 아이-트래킹(eye tracking)과 대뇌 피질 활동은 최대치로 분주해진다. 만일 작품의 제목까지도 눈여겨보는 관람객이라면, 어딘가 시니컬한 유머가 깃든 제목 정보까지, 전시는 압축되고 승화된 결정체이기보다 답하기 어려운 질문들을 자꾸만 불러내는 미완태에 가깝다.

박경률의 최근 회화들은 이미 화면 안에서부터 전경과 후경, 중심과 주변, 손이 알아서 재빨리 그어낸 선과 머리로 구상하고 정성을 다해 채운 면적, 추상과 구상 등 위계와 선후를 정할 수 없는 비 결정적 내러티브 구조를 지향한다. 회화-설치의 원 재료들이 1차 제작된 스튜디오를 떠나 주어진 공간에서의 ‘설치’ 과정을 거치면서 작업의 재료들은 새로운 관람 구조로 재편된다. 그 속에서 끌리는 파편들을 골라내고, 더 큰 덩어리로 이어내어 일종의 집합을 완성하고, 최후의 심상과 서사를 종합해 내는 일은 결국 관람객의 몫이 된다.

평평하고, 균일한 특질의 회화 전시를 기대하며 온 이들에게는 어쩐지 ‘Even’해 보이지 않는 이번 전시에서 작가가 숙고했던 “Evenness”는 어떤 의미였을까. 번역하기에 따라 균질, 균일, 균등의 단어로 이해되기도 하는 “Evenness”는 지난 여름 런던의Lungley 갤러리에서 선보였던 동명의 전시에서 다루어진 적이 있는다. 작가는 화면 속의 붓질 하나하나, 재현되거나 추상된 이미지, 공간 속의 오브제, 공간을 이루는 자연적/인공적 요소들 마저 모두 작품의 총체적 이미지와 내러티브를 촉발시키는 개별적이고 “동등한” 회화적 조건으로 규정하고 있다. 울퉁불퉁한 조건들을 동등한 요소들로 받아들일 때, 회화를 작동시키는 관습적 적용과 창작술을 허물어 버리는 역설이 발생하게 되는 셈이다.

회화를 회화로, 작업을 작업으로, 나아가 전시를 전시로 소비하게 만드는 것이 기실 엄청난 우연과 무연이 개입된 복잡한 조건들이며, 그럼에도 그토록 익숙한 예술 생산과 수용의 토대를 벗어나기 어렵다는 것을 작가도, 우리도 알고 있다. 다만, 자기 작업의 역사와 당위를 다른 각도에서 되묻고, 변화된 실천을 해나가는 박경률의 고민과 궁리로부터 어떤 전망을 해볼법한 단서들을 추려본다. 작가들이 전통적인 이미지메이커로서 붙들려 있는 역할 수행과 전시방법으로부터 새로운 방식을 모색해 나가는 시도들을 주시하며, 그들이 어떻게 스스로의 작품과 전시의 룰 메이커가 되고, 이미지 소스를 다루는 공간 속의 DJ 혹은 사이퍼cypher가 되는지, 이윽고 변화하는 시대에 대응하는 시각적 저자로 이행해 나가게 될지 미루어 그려보게 된다.

Exhibition Review; 어떤 회화의 동선 <박경률_ON EVENNESS> _ 조은채 (예술학), 2019

문득 ‘명화’를 가장 가까이에서 볼 수 있는 방법이 된 구글의 ‘아트 카메라(Art Camera)’가 떠올랐다. 기가픽셀 카메라와 각종 신기술을 거쳐 재조합된 아트 카메라 속 명화의 초고해상도 이미지. 화면을 확대하면 물감을 덧칠한 흔적까지 선명하게 보이고 실물을 보는 것보다 오히려 더 사실적으로 느껴진다. 픽셀로 이루어진 화면 속의 이미지를 보며 회화의 물성을 감각하는 일은 어쩐지 모순적이다. 박경률의 웹사이트에서도 이번 개인전 <ON EVENNESS>의 1층부터 3층을 구석구석 담은 사진을 확인할 수 있다. 이 웹사이트에는 전시장을 방문했을 때보지 못하고 지나칠 수 있는 부분마저도 꼼꼼하게 사진으로 기록되어 있고 시간의 제약 없이 작품을 들여다볼 수도 있다. 구글의 아트 카메라를 통해 실제보다 더 나은 환경에서 명화를 접할 때처럼, 오히려 웹사이트에서 <ON EVENNESS>를 더 온전하고 자세하게 관람할 수 있을 것 같다는 착각이 든다. 물론, 아트 카메라와 박경률의 웹사이트가 불러일으키는 이 감각의 역전을 단순한 착시라고 일축할 수만은 없을 것이다. 하지만 <ON EVENNESS>에는 방문이 전제되어야만 경험할 수 있는 무언가가 있을지도 모른다.

박경률의 회화에는 현실의 대상을 연상하게 하는 여러 이미지가 층층이 겹쳐 있다. 그러나 이 다양한 이미지의 등장에는 아무런 규칙이 없는 것처럼 보인다. 관람객은 이 이미지들이 하나의 표면에 놓일 수 있는 이유를 해명하기 위해 회화를 해석하려고 시도한다. 회화 안의 내러티브를 찾으려고 하는 것이다. 이때 시간과 공간의 제약 없이 전시의 모든 면면을 살펴볼 수 있는 웹사이트는 최적의 감상 장소가 된다. 하지만 박경률은 ‘내러티브가 부재’한 것을 ‘마치 있는 것처럼 연출’하면 어떻게 될지 질문을 던지며 이번 전시를 구성했다고 밝힌다. 회화를 읽고 해석하는, 즉 실물의 회화가 아닌 화면 속의 이미지로도 가능한 이 감상법은 이제 박경률의 작업을 보는 적절한 방식이 아닌 것처럼 느껴진다. 어쩌면 전시라는 제한된 환경 속에서 실물을 마주해야만 할 수 있는 경험이 <ON EVENNESS>를 정확하게 감상하는 방법과 연동되는 게 아닐까?

<ON EVENNESS>에는 회화 외에도 과일, 종이, 꽃, 세라믹 조각과 같은 오브제가 군데군데 놓여있다. 이 수많은 오브제는 박경률의 회화 표면을 연상하게 하는데, 서로 연관성이 희미해 보이는 요소들이 한 장소에 별다른 규칙 없이 출현하는 것처럼 느껴지기 때문이다. 박경률의 회화 속 이미지를 조형해 놓은 것 같은 이 오브제들은 특별히 신경 쓰지 않으면 지나쳐버릴 모퉁이에 놓여있기도 하고, 회화의 연장인 것처럼 캔버스와 맞붙어 있거나, 또는 고개를 올려야 보일 만큼 꼭대기에 매달려있기도 한다. 도면은 보통 전시를 보는 경로를 어느 정도 지정해 주지만 <ON EVENNESS>에는 따로 도면이 없다. 이번 전시를 찾은 관람객은 저마다 스스로 동선을 만들어나가겠지만 아마도 1층에서는 벽면을 가득 채운 회화 <Revolving figure>를 감상하다가 이 작업을 받치고 있는 오렌지를 느닷없이 발견하고 웃음이 날지도 모른다. 2층에서는 바닥과 벽, 그리고 회화에 붙어 있는 형형색색의 오브제를 밟거나 건드리지 않기 위해서 평소보다 조심스럽게 움직여야 한다. 3층에서는 커다란 창문으로 들어오는 빛에 따라 회화에 부여되는 새로운 각도를 보기 위해 자리를 자주 옮기게 될지도 모른다. 그리고 박경률이 자신의 작업을 설명했던 “조각적 회화”라는 말이 떠오를 것이다. 박경률에게 조각적 회화는 완성된 회화 작품 자체, 회화 속의 붓질 하나, 바닥에 놓인 과일, 유리창을 통해 들어오는 빛 등 모든 요소를 동등하고 개별적인 오브제로 여기는 것을 의미한다. <ON EVENNESS>에서 박경률은 마치 하나의 회화를 구성하는 것처럼 전시 공간 역시 하나의 평면으로 가정하고 각각의 요소를 배치한다. 작가가 관람객에게 회화를 보는 시선의 경로를 제시하지 않듯이, 전체 도면이 주어지지 않은 것은 <ON EVENNESS>가 전시인 동시에 그 자체로 하나의 회화가 되었기 때문인지도 모른다. 회화 속 각각의 요소에서 그 중요도를 헤아리거나 이면의 의미를 알아내려고 노력하며 해석할 거리를 찾는 대신에, 오브제로서 균등한 대상들 사이를 거닐고 또 옮겨 다니며 회화를 있는 그대로 감각하는 것. 이것이 모니터 너머의 사진으로는 불가능하지만 전시라는 환경에서는 가능한 경험이자 박경률의 회화와 <ON EVENNESS>를 정확하게 보는 방법일 것이다.

균질성을 지니는 회화는 가능한가

박경률 개인전:On Evenness_ 김인선 (스페이스 윌링앤딜링 디렉터), 2019

2018년 송은아트스페이스에서 선보인 박경률 작가의 회화는 온전한 평면 회화를 기대한 관객들에게는 당혹감을 주었을 것이다. 거대한 캔버스 주변으로 놓여진 것들은 과일, 각목, 액자 프레임 등의 일상의 오브제들이기도 하였고, 물감으로 채색된 비정형의 덩어리들이 놓여있는가 하면, 그림 주변 벽면에 부착된 받침대 위에 놓인 또 다른 덩어리들은 서로 분리되어 있되 하나로 묶인 단위처럼 보이기도 하였다. 이 작가의 공간은 하나의 거대한 설치로서 보이기도 하였고, 그림 속에서 빠져나온 이미지들은 작은 크기의 캔버스나 종이 위로 그려진 채, 그리고 여기 저기 놓인 덩어리의 형태로서 공간 점유를 시도하는 듯 보이기도 했다. 이 공간 속에서 혹자는 그가 회화 작가인지 설치작가인지 잠시 혼란에 빠졌을 지도 모른다. 작가를 붙잡고 이야기를 해보아도 점점 미궁으로 빠질 수 있다. 그는 장르적 접근보다는 자신이 그리고 있는 혹은 만들고 있는 이미지가 어떻게 예술로서 조응할 수 있는지에 대한 고민들 털어놓기 때문이다. 하지만 이내 그의 연구는 모두 회화적인 것에 귀결되어 있다는 것을 알수있다.

그는 '조각적 회화'라는 용어를 꾸준히 언급해 왔다. 회화를 조각적으로 혹은 조각을 회화의 영역 안에서 교차시키는 시도는 직접 오브제를 다루지 않았던 2008년 - 2012년까지의 초기 작업 속에서도 드러난다. 이 기간동안 그려진 대형 회화에서는 대체로 캔버스 화면과 벽 혹은 바닥으로 나뉘어진 화면 구성을 쉽게 찾아볼 수 있다. 그림 속 캔버스와 전시 공간에 놓여진 실재 캔버스는 구분하여 지칭하는데에도 혼란을 겪는다. 그의 회화 속 이미지 또한 거대한 캔버스와 그 속에 존재하는 그려진 캔버스 위로 펼쳐진 공간으로서, 이미지 속의 회화를 그린 것인지 혹은 캔버스와 마루바닥 사이에서 부유하는 덩어리들을 그린 것인지 다시 한번 혼란스럽다. 구체적인 형상으로서 재현되어 화면 전체를 메우고 있는 이 이미지들은 회화 속에 또 다른 공간이 존재하고 있는 듯 우리의 눈을 두서 없이 쫓도록 만든다. 작가는 캔버스 앞에서 자신의 머리를 헤집으면서 끄집어낸 기억의 파편들을 늘어놓았다. 그는 지극히 직관적으로 이들을 배치하는데, 특정한 경험의 기억 속 오브제를 시작으로 꼬리와 꼬리를 물고 오브제들 사이의 공간을 만들어낸다. 이들은 알 수 없는 공간 속에 부유하며 서로의 관계를 상상하게 한다. 이렇게 만들어진 공간 사이사이로 다시 채워지는 오브제들, 기억의 이미지들은 연결선이 생략된 거대한 구조물처럼 부유하는 덩어리가 된다. 다시 이 화면을 분할하고 있는 벽면과 바닥으로 눈이 머물때, 캔버스 앞에서 상상력을 발휘하고 있는 작가의 모습으로 돌아가게 한다.

회화 전공을 하면서 캔버스를 대하는 동안 박경률 작가는 자신이 다루는 붓의 움직임, 선, 색 등이 만들어낸 이미지가 예술로서 의미를 가지는 이유에 대한 고민을 해왔다고 했다. 직관과 본능적인 그리기에 대한 탐구는 스스로를 제삼자로 놓고 객관적인 입장에서 무의식적 그리기에 대한 관찰을 시도할 수 있는 실험을 궁리하도록 이끈다. 그리고2013년 겨울, 스페이스 윌링앤딜링에서의 전시를 위하여 치매 노인들과 함께 그리기 프로젝트를 실행하였다. 영상 도큐멘터리와 회화, 설치, 드로잉 등 작가가 다루는 매체는 다양했다. 치매 노인들과의 정기적인 만남으로 그들의 이야기를 들었고, 이를 기반으로 영상 작업을 진행했다.동시에 그들의 기억을 환기하게 하는 드로잉을 그리게 하면서 작가의 개입이 발현되는 거대한 드로잉 또한 제작되었다. 프로젝트를 시작하면서 본능적인 그리기와 논리가 없는 허구의 이미지를 기대하였던 작가는 놀라운 사실을 경험하였다. 치매 노인들의 이야기는 기승전결이 명확한 기억이었고, 나름의 논리성이 드로잉에도 반영되었다. 이 프로젝트 이후로 그는 무의식의 행위와 예술 행위가 맞닿아 있을 것이라는 막연한 기대로부터 벗어났다. 공간 속 레이어들을 드러내면서 쌓였던 기억의 파편으로 존재하였던 이미지는 그 중량감과 부피감을 제거하며 점차 표면 자체로 환원되는 현상을 보여주었다. 이는 영국 유학시절, 자신의 그림이 어떠한 차별성을 가질 수 있는지에 대한 고민에서 나온 해결 방법이기도 하였다. 이전 이미지에서 보여준 재현적 묘사로부터 발생하는 이미지의 부피와 무게에 대한 감각, 그리고 네러티브를 유도하는 기억의 파편 속에서 불러들인 이미지에서 그 내용을 삭제하였고 이미지 요소인 선, 색 등만을 남겨두는 변화를 준 것이다. 그리하여 물질감과 네러티브는 삭제되었다. 이들이 제거된 화면 위에는 선과 색 등 재료 자체와 페인터의 몸에서 발생하는 본질적 회화 요소가 강조되어 있다. 한붓에 슥슥 그려낸 형상들은 그 출처를 알 수 없는 특정 캐릭터와 같은 모양을 형성하고 있다. 의미를 알 수 없는 문자처럼 그려진 선들은 동양의 칼리그래피의 요소를 환기시키며 기호 표기에 대한 해석을 시도하는데에 익숙한 관람객의 의식을 교란시킨다.